原文:

https://craftinginterpreters.com/a-map-of-the-territory.html

You must have a map, no matter how rough. Otherwise you wander all over the place. In The Lord of the Rings I never made anyone go farther than he could on a given day.

— J. R. R. Tolkien

你必须有一张地图,无论多么粗糙。 不然你就到处乱逛。 在《指环王》中,我从未让任何人在某一天走得比他能走得更远。

— J·R·R·托尔金

We don’t want to wander all over the place, so before we set off, let’s scan the territory charted by previous language implementers. It will help us understand where we are going and the alternate routes others have taken.

我们不想到处乱逛,所以在出发之前,让我们先浏览一下以前的语言实现者绘制的领土。 它将帮助我们了解我们要去哪里以及其他人采取的备选路线。

First, let me establish a shorthand. Much of this book is about a language’s implementation, which is distinct from the language itself in some sort of Platonic ideal form. Things like “stack”, “bytecode”, and “recursive descent”, are nuts and bolts one particular implementation might use. From the user’s perspective, as long as the resulting contraption faithfully follows the language’s specification, it’s all implementation detail.

首先,让我先做个简单说明。 本书的大部分内容都是关于语言的实现,这与某种柏拉图理想形式的语言本身不同。 诸如“堆栈”、“字节码”和“递归下降”之类的东西是一种特定实现可能使用的具体细节。 从用户的角度来看,只要最终的装置忠实地遵循语言的规范,这些都是他们并不关心的实现细节罢了。

We’re going to spend a lot of time on those details, so if I have to write “language implementation” every single time I mention them, I’ll wear my fingers off. Instead, I’ll use “language” to refer to either a language or an implementation of it, or both, unless the distinction matters.

我们将在这些细节上花费大量时间,因此,如果我每次提到它们时都必须编写“语言实现”,我的手指就废了。 相反,我将使用“语言”来指代一种语言或它的实现,或两者,除非确实需要区别。

2.1 The Parts of a Language

Engineers have been building programming languages since the Dark Ages of computing. As soon as we could talk to computers, we discovered doing so was too hard, and we enlisted their help. I find it fascinating that even though today’s machines are literally a million times faster and have orders of magnitude more storage, the way we build programming languages is virtually unchanged.

自计算的黑暗时代以来,工程师们一直在构建编程语言。 当我们能够与计算机对话时,我们发现这样做太难了,于是我们寻求了电脑的帮助。 我觉得很有趣的是,尽管今天的机器速度确实快了一百万倍,并且存储量增加了几个数量级,但我们构建编程语言的方式几乎没有改变。

Though the area explored by language designers is vast, the trails they’ve carved through it are few. Not every language takes the exact same path—some take a shortcut or two—but otherwise they are reassuringly similar, from Rear Admiral Grace Hopper’s first COBOL compiler all the way to some hot, new, transpile-to-JavaScript language whose “documentation” consists entirely of a single, poorly edited README in a Git repository somewhere.

尽管语言设计者探索的领域很广阔,但他们在其中开辟的道路却很少。 并不是每种语言都走完全相同的道路——有些语言走了一两条捷径——但在其他方面它们非常相似,从海军少将 Grace Hopper 的第一个 COBOL 编译器一直到一些热门的、新的、可转译为 JavaScript 的语言(其“文档” 甚至完全由 Git 上某个地方的一个简陋的 README 组成)。

There are certainly dead ends, sad little cul-de-sacs of CS papers with zero citations and now-forgotten optimizations that only made sense when memory was measured in individual bytes.

CS 论文当然也存在死胡同,零引用的悲惨小众论文,以及现在被遗忘的优化方法,这些优化只有在以单个字节来衡量内存时才有意义。

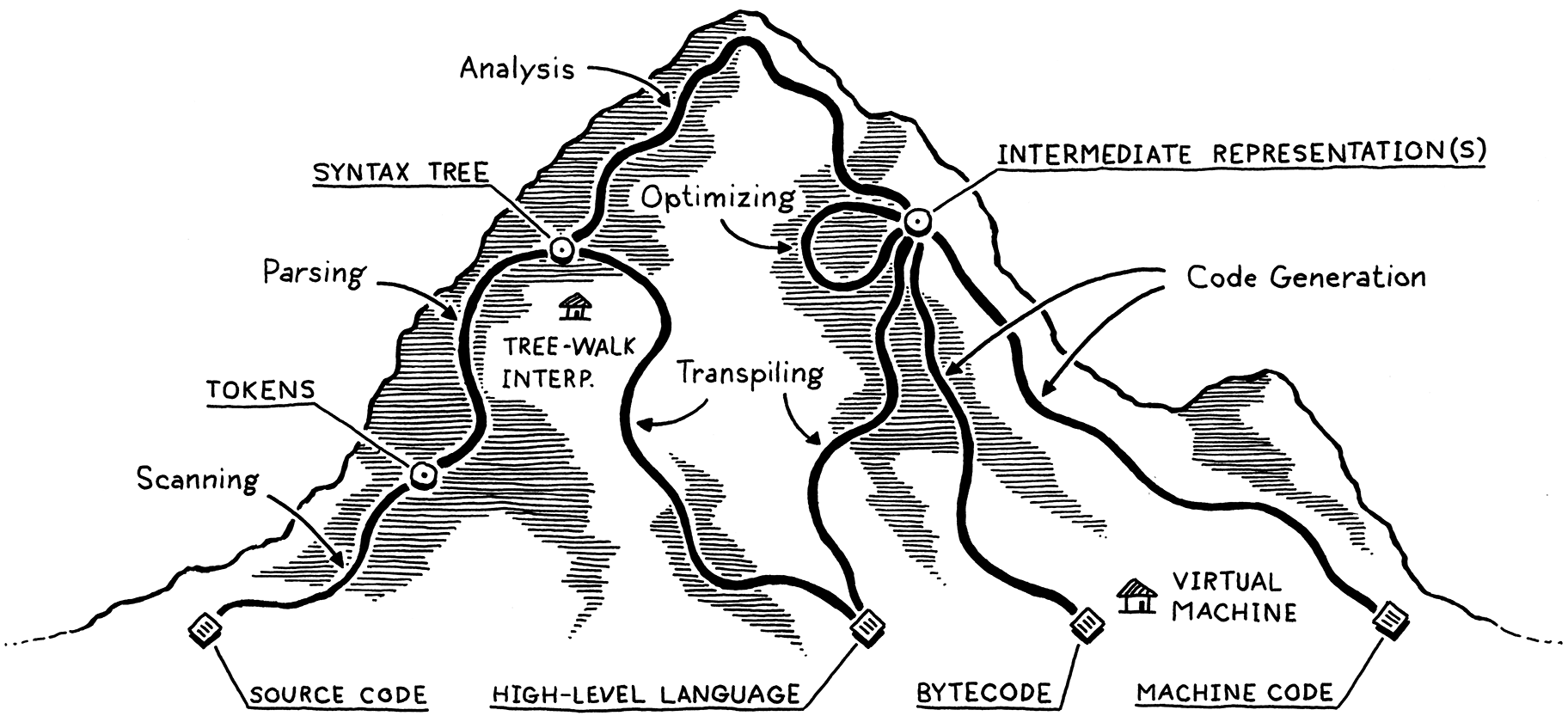

I visualize the network of paths an implementation may choose as climbing a mountain. You start off at the bottom with the program as raw source text, literally just a string of characters. Each phase analyzes the program and transforms it to some higher-level representation where the semantics—what the author wants the computer to do—become more apparent.

我将语言实现可能选择的路径网络想象为爬山。 你从底部开始将程序作为原始源文本,实际上只是一串字符。 每个阶段都会分析程序并将其转换为某种更高级别的表示,从而使语义(作者希望计算机执行的操作)变得更加明显。

Eventually we reach the peak. We have a bird’s-eye view of the user’s program and can see what their code means. We begin our descent down the other side of the mountain. We transform this highest-level representation down to successively lower-level forms to get closer and closer to something we know how to make the CPU actually execute.

最终我们到达了顶峰。 我们可以鸟瞰用户的程序,可以看到他们的代码的含义。 我们开始从山的另一边下山。 我们将这种最高级别的表示形式依次转换为较低级别的形式,以越来越接近我们知道如何让 CPU 实际执行的东西。

Let’s trace through each of those trails and points of interest. Our journey begins on the left with the bare text of the user’s source code:

让我们追踪每一条路线和兴趣点。 我们的旅程从用户源代码的左侧裸文本开始:

2.1.1 Scanning

The first step is scanning, also known as lexing, or (if you’re trying to impress someone) lexical analysis. They all mean pretty much the same thing. I like “lexing” because it sounds like something an evil supervillain would do, but I’ll use “scanning” because it seems to be marginally more commonplace.

第一步是扫描,也称为词法分析,或者(如果你想给某人留下深刻印象)词法的分析。 它们的含义几乎相同。 我喜欢“词法分析”,因为它听起来像是邪恶的超级恶棍会做的事情,但我会使用“扫描”,因为它似乎更常见。

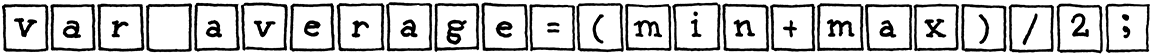

A scanner (or lexer) takes in the linear stream of characters and chunks them together into a series of something more akin to “words”. In programming languages, each of these words is called a token. Some tokens are single characters, like ( and ,. Others may be several characters long, like numbers (123), string literals (“hi!”), and identifiers (min).

扫描器(或词法分析器)接收线性字符流,并将它们组合成一系列更类似于“单词”的东西。 在编程语言中,每个单词都称为一个词法单元。 有些词法单元是单个字符,例如 ( 和 , 。其他的词法单元可能是多个字符,例如数字 123、字符串文字 "hi!" 和标识符 min。

“Lexical” comes from the Greek root “lex”, meaning “word”.

“Lexical”源自希腊语词根“lex”,意思是“单词”。

Some characters in a source file don’t actually mean anything. Whitespace is often insignificant, and comments, by definition, are ignored by the language. The scanner usually discards these, leaving a clean sequence of meaningful tokens.

源文件中的某些字符实际上没有任何意义。 空格通常是无关紧要的,并且根据定义,注释会被语言忽略。 扫描仪通常会丢弃这些标记,只留下有意义的词法单元构成的干净序列。

2.1.2 Parsing

The next step is parsing. This is where our syntax gets a grammar—the ability to compose larger expressions and statements out of smaller parts. Did you ever diagram sentences in English class? If so, you’ve done what a parser does, except that English has thousands and thousands of “keywords” and an overflowing cornucopia of ambiguity. Programming languages are much simpler.

下一步是解析。 这就是我们从句法中得到语法的地方——语法能够将较小的部分组成更大的表达式和语句。 你在英语课上做过语法图解吗? 如果有,你就完成了解析器所做的事情,只不过英语有成千上万的“关键字”和大量的歧义,而编程语言要简单得多。

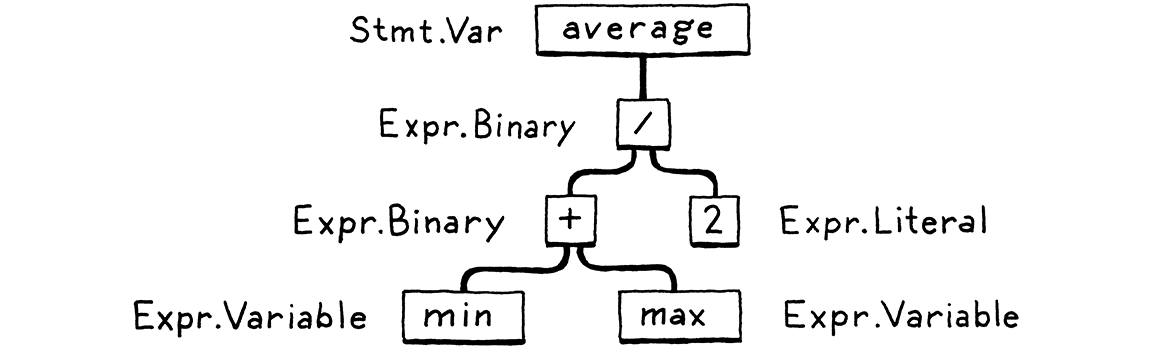

A parser takes the flat sequence of tokens and builds a tree structure that mirrors the nested nature of the grammar. These trees have a couple of different names—parse tree or abstract syntax tree—depending on how close to the bare syntactic structure of the source language they are. In practice, language hackers usually call them syntax trees, ASTs, or often just trees.

解析器将平坦的词法单元序列转化成可以反映语法嵌套性质的树结构。 这些树有几个不同的名称——解析树或抽象语法树——具体取决于它们与源语言的裸语法结构的接近程度。 在实践中,语言黑客通常将它们称为语法树、AST,或者通常简称为树。

Parsing has a long, rich history in computer science that is closely tied to the artificial intelligence community. Many of the techniques used today to parse programming languages were originally conceived to parse human languages by AI researchers who were trying to get computers to talk to us.

解析在计算机科学领域有着悠久而丰富的历史,与人工智能界密切相关。 如今用于解析编程语言的许多技术最初是由试图让计算机与我们对话的人工智能研究人员构想的,原本是用于解析人类语言。

It turns out human languages were too messy for the rigid grammars those parsers could handle, but they were a perfect fit for the simpler artificial grammars of programming languages. Alas, we flawed humans still manage to use those simple grammars incorrectly, so the parser’s job also includes letting us know when we do by reporting syntax errors.

事实证明,人类语言对于只能处理僵化语法的解析器来说太混乱了,但这些解析器非常适合编程语言这样简单的人工语法。 唉,我们这些有缺陷的人类在使用这些简单语法时仍然不停地出错,因此解析器的工作还包括报告语法错误来让我们知道出错了。

2.1.3 Static analysis

The first two stages are pretty similar across all implementations. Now, the individual characteristics of each language start coming into play. At this point, we know the syntactic structure of the code—things like which expressions are nested in which—but we don’t know much more than that.

所有语言实现中的前两个阶段都非常相似。 现在,每种语言的特性开始发挥作用。 至此,我们知道了代码的语法结构(例如哪些表达式嵌套在哪个表达式中),但除此之外我们所知不多。

In an expression like a + b, we know we are adding a and b, but we don’t know what those names refer to. Are they local variables? Global? Where are they defined?

在像 a + b 这样的表达式中,我们知道要添加 a 和 b ,但我们不知道这些名称指的是什么。 它们是局部变量吗? 全局变量? 它们在哪里定义的?

The first bit of analysis that most languages do is called binding or resolution. For each identifier, we find out where that name is defined and wire the two together. This is where scope comes into play—the region of source code where a certain name can be used to refer to a certain declaration.

大多数语言所做的第一个分析称为绑定或决议。 对于每个标识符,我们都要找到定义该名称的地方,并将两者连接在一起。 这就是作用域的作用——在这个源代码的区域中,某个名称可以用来引用某个声明。

If the language is statically typed, this is when we type check. Once we know where a and b are declared, we can also figure out their types. Then if those types don’t support being added to each other, we report a type error.

如果语言是静态类型的,这就是我们进行类型检查的时机。 一旦我们知道了 a 和 b 的声明位置,我们就可以找出它们的类型。 如果这些类型不支持相加,我们就会报告一个类型错误。

The language we’ll build in this book is dynamically typed, so it will do its type checking later, at runtime.

我们将在本书中构建的语言是动态类型的,因此将在稍后的运行时中进行类型检查。

Take a deep breath. We have attained the summit of the mountain and a sweeping view of the user’s program. All this semantic insight that is visible to us from analysis needs to be stored somewhere. There are a few places we can squirrel it away:

深吸一口气。 我们已经登上了山顶,对用户的程序一览无余。 通过分析可以看到的所有语义信息都需要存储在某个地方。 我们可以将其存放在几个地方:

-

Often, it gets stored right back as attributes on the syntax tree itself—extra fields in the nodes that aren’t initialized during parsing but get filled in later.

-

通常,它会被直接存储在语法树本身的属性上——属性是节点中的额外字段,这些字段在解析过程中不会初始化,但稍后会进行填充。

-

Other times, we may store data in a lookup table off to the side. Typically, the keys to this table are identifiers—names of variables and declarations. In that case, we call it a symbol table and the values it associates with each key tell us what that identifier refers to.

-

有时,我们可能会将数据存储在外部的查找表中。 通常,该表的键是标识符,即变量的名称和声明。 在这种情况下,我们将其称为符号表,表中每个键关联的值会告诉我们该标识符指的是什么。

-

The most powerful bookkeeping tool is to transform the tree into an entirely new data structure that more directly expresses the semantics of the code. That’s the next section.

-

最强大的记录工具就是将树转变成一种全新的数据结构,更直接地表达代码的语义。 这是下一节的内容。

Everything up to this point is considered the front end of the implementation. You might guess everything after this is the back end, but no. Back in the days of yore when “front end” and “back end” were coined, compilers were much simpler. Later researchers invented new phases to stuff between the two halves. Rather than discard the old terms, William Wulf and company lumped those new phases into the charming but spatially paradoxical name middle end.

到目前为止的一切都被认为是语言实现的前端。 你可能会猜测在这之后的一切就是后端,但事实并非如此。 回到过去“前端”和“后端”被创造出来的时候,编译器要简单得多。 后来研究人员在两个半部之间引入了新阶段。 威廉·沃尔夫(William Wulf)和他的同伴并没有放弃旧术语,而是新添加了一个迷人但有点自相矛盾的名称中端。

2.1.4 Intermediate representations

中间码

You can think of the compiler as a pipeline where each stage’s job is to organize the data representing the user’s code in a way that makes the next stage simpler to implement. The front end of the pipeline is specific to the source language the program is written in. The back end is concerned with the final architecture where the program will run.

你可以将编译器视为一个管道,每个阶段的工作是把代表用户代码的数据组织起来,使下一阶段的实现更加简单。 管道的前端是针对编写程序所用的源语言编写的。后端关注的是程序运行的最终架构。

In the middle, the code may be stored in some intermediate representation (IR) that isn’t tightly tied to either the source or destination forms (hence “intermediate”). Instead, the IR acts as an interface between these two languages.

在中间阶段,代码可能存储在某种中间代码 (intermediate representation, 也叫 IR) 中,该中间代码与源文件或最终目标文件形式没有紧密的联系(因此称为“中间”)。 相反,IR 充当这两种语言之间的接口。

There are a few well-established styles of IRs out there. Hit your search engine of choice and look for “control flow graph”, “static single-assignment”, “continuation-passing style”, and “three-address code”.

有一些成熟的 IR 风格。 点击你选择的搜索引擎并查找“控制流图”、“静态单赋值”、“延续传递形式”和“三位址码”。

This lets you support multiple source languages and target platforms with less effort. Say you want to implement Pascal, C, and Fortran compilers, and you want to target x86, ARM, and, I dunno, SPARC. Normally, that means you’re signing up to write nine full compilers: Pascal→x86, C→ARM, and every other combination.

这使你可以轻松支持多种源语言和目标平台。 假设你想要实现 Pascal、C 和 Fortran 编译器,并且想要以 x86、ARM 和 SPARC(我不知道)为目标。 通常,这意味着你要编写九个完整的编译器:Pascal→x86、C→ARM 以及所有其他组合。

A shared intermediate representation reduces that dramatically. You write one front end for each source language that produces the IR. Then one back end for each target architecture. Now you can mix and match those to get every combination.

一个共享的中间代码可以极大地减少这种情况。 你为生成 IR 的每种源语言编写一个前端。 然后为每个目标平台写一个后端。 现在,你可以将它们混搭起来,获得每一种组合。

If you’ve ever wondered how GCC supports so many crazy languages and architectures, like Modula-3 on Motorola 68k, now you know. Language front ends target one of a handful of IRs, mainly GIMPLE and RTL. Target back ends like the one for 68k then take those IRs and produce native code.

如果你曾经想知道 GCC 如何支持如此多疯狂的语言和架构,例如 Motorola 68k 上的 Modula-3,现在你就明白了。 语言前端针对的是少数 IR ,主要是 GIMPLE 和 RTL。 目标后端(例如 68k 的后端)会获取这些 IR 并生成本机代码。

There’s another big reason we might want to transform the code into a form that makes the semantics more apparent…

我们可能希望将代码转换为一种使语义更加明显的形式还有另一个重要原因……

2.1.5 Optimization

Once we understand what the user’s program means, we are free to swap it out with a different program that has the same semantics but implements them more efficiently—we can optimize it.

一旦我们理解了用户程序的含义,我们就可以自由地将其替换为具有相同语义但更高效地实现它们的不同程序——我们可以优化它。

A simple example is constant folding: if some expression always evaluates to the exact same value, we can do the evaluation at compile time and replace the code for the expression with its result. If the user typed in this:

一个简单的例子是常量折叠:如果某个表达式总是计算出完全相同的值,我们可以在编译时进行计算,并用其结果替换表达式的代码。 如果用户输入以下内容:

pennyArea = 3.14159 * (0.75 / 2) * (0.75 / 2);

we could do all of that arithmetic in the compiler and change the code to:

我们可以在编译器中完成所有算术并将代码更改为:

pennyArea = 0.4417860938;

Optimization is a huge part of the programming language business. Many language hackers spend their entire careers here, squeezing every drop of performance they can out of their compilers to get their benchmarks a fraction of a percent faster. It can become a sort of obsession.

优化是编程语言业务的重要组成部分。 许多语言黑客将他们的整个职业生涯都花在了这里,从编译器中榨取每一滴性能,以使他们的基准测试速度提高百分之一。 这可能会上瘾。

We’re mostly going to hop over that rathole in this book. Many successful languages have surprisingly few compile-time optimizations. For example, Lua and CPython generate relatively unoptimized code, and focus most of their performance effort on the runtime.

在这本书中,我们通常会跳过那个老鼠洞。 许多成功的语言几乎没有编译时优化。 例如,Lua 和 CPython 生成相对未优化的代码,并将大部分性能工作集中在运行时。

If you can’t resist poking your foot into that hole, some keywords to get you started are “constant propagation”, “common subexpression elimination”, “loop invariant code motion”, “global value numbering”, “strength reduction”, “scalar replacement of aggregates”, “dead code elimination”, and “loop unrolling”.

如果你无法抗拒将脚伸进那个洞,那么可以帮助你入门的一些关键字是“常量折叠”、“公共表达式消除”、“循环不变代码外提”、“全局值编号”、“强度降低”、“ 聚合量标量替换”、“死代码删除”和“循环展开”。

2.1.6 Code generation

We have applied all of the optimizations we can think of to the user’s program. The last step is converting it to a form the machine can actually run. In other words, generating code (or code gen), where “code” here usually refers to the kind of primitive assembly-like instructions a CPU runs and not the kind of “source code” a human might want to read.

我们已经将所有能想到的优化应用到了用户的程序中。 最后一步是将其转换为机器可以实际运行的形式。 换句话说,生成代码(或代码生成),这里的“代码”通常指的是 CPU 运行的原始汇编指令,而不是人类可能想要阅读的“源代码”。

Finally, we are in the back end, descending the other side of the mountain. From here on out, our representation of the code becomes more and more primitive, like evolution run in reverse, as we get closer to something our simple-minded machine can understand.

最后,我们到了后端,从山的另一边下山。 从现在开始,当我们越来越接近我们头脑简单的机器可以理解的东西时,我们对代码的表示变得越来越原始,就像逆向进化一样。

We have a decision to make. Do we generate instructions for a real CPU or a virtual one? If we generate real machine code, we get an executable that the OS can load directly onto the chip. Native code is lightning fast, but generating it is a lot of work. Today’s architectures have piles of instructions, complex pipelines, and enough historical baggage to fill a 747’s luggage bay.

我们需要做出决定。 我们是为真实的 CPU 还是虚拟的 CPU 生成指令? 如果我们生成真实的机器代码,我们就会获得操作系统可以直接加载到芯片上的可执行文件。 本机代码速度快如闪电,但生成它需要大量工作。 今天的体系结构有成堆的指令、复杂的管道,以及足以填满一架 747 行李舱的历史包袱。

Speaking the chip’s language also means your compiler is tied to a specific architecture. If your compiler targets x86 machine code, it’s not going to run on an ARM device. All the way back in the ’60s, during the Cambrian explosion of computer architectures, that lack of portability was a real obstacle.

使用芯片的语言还意味着你的编译器与特定的架构相关联。 如果你的编译器以 x86 机器代码为目标,则它无法在 ARM 设备上运行。 早在 20 世纪 60 年代,在计算机架构的寒武纪大爆发期间,缺乏可移植性是一个真正的障碍。

For example, the AAD (“ASCII Adjust AX Before Division”) instruction lets you perform division, which sounds useful. Except that instruction takes, as operands, two binary-coded decimal digits packed into a single 16-bit register. When was the last time you needed BCD on a 16-bit machine?

例如,AAD(“ASCII Adjust AX Before Division”)指令可让你执行除法,这听起来很有用。 只不过该指令将两个二进制编码的十进制数字打包到一个 16 位寄存器中作为操作数。 你最后一次在 16 位计算机上需要二进制编码的十进制数是什么时候?

To get around that, hackers like Martin Richards and Niklaus Wirth, of BCPL and Pascal fame, respectively, made their compilers produce virtual machine code. Instead of instructions for some real chip, they produced code for a hypothetical, idealized machine. Wirth called this p-code for portable, but today, we generally call it bytecode because each instruction is often a single byte long.

为了解决这个问题,Martin Richards 和 Niklaus Wirth 等分别以 BCPL 和 Pascal 闻名的黑客让他们的编译器生成虚拟机代码。 他们没有为某个真实芯片生成指令,而是为假设的理想化机器生成代码。 Wirth 将这种 p-code 称为可移植代码,但今天,我们通常将其称为字节码,因为每条指令通常都是单字节长。

These synthetic instructions are designed to map a little more closely to the language’s semantics, and not be so tied to the peculiarities of any one computer architecture and its accumulated historical cruft. You can think of it like a dense, binary encoding of the language’s low-level operations.

这些合成指令的设计目的是为了更紧密地映射语言的语义,而不必与任何一种计算机体系结构的特性及其积累的历史错误紧密地联系在一起。 你可以将其视为该语言的低级操作的密集二进制编码。

2.1.7 Virtual machine

If your compiler produces bytecode, your work isn’t over once that’s done. Since there is no chip that speaks that bytecode, it’s your job to translate. Again, you have two options. You can write a little mini-compiler for each target architecture that converts the bytecode to native code for that machine. You still have to do work for each chip you support, but this last stage is pretty simple and you get to reuse the rest of the compiler pipeline across all of the machines you support. You’re basically using your bytecode as an intermediate representation.

如果你的编译器生成字节码,那么你的工作一旦完成就还没有结束。 由于没有芯片可以解析这些字节码,因此你还需要进行翻译。 同样,你有两个选择。 你可以为每个目标体系结构编写一个小型编译器,将字节码转换为该机器的本机代码。 你仍然需要为你支持的每个芯片做一些工作,但是最后一个阶段非常简单,你可以在你支持的所有机器上重用编译器流水线的其余部分。 你基本上是把你的字节码作为一种中间代码。

The basic principle here is that the farther down the pipeline you push the architecture-specific work, the more of the earlier phases you can share across architectures.

这里的基本原则是,你将特定于体系架构的工作推得越靠后,可以拿来跨架构共享的早期阶段就越多。

There is a tension, though. Many optimizations, like register allocation and instruction selection, work best when they know the strengths and capabilities of a specific chip. Figuring out which parts of your compiler can be shared and which should be target-specific is an art.

不过,这里存在一些矛盾。 许多优化(例如寄存器分配和指令选择)在了解特定芯片的优势和功能以后才能达到最佳效果。 弄清楚编译器的哪些部分可以共享,哪些部分应该针对特定目标是一门艺术。

Or you can write a virtual machine (VM), a program that emulates a hypothetical chip supporting your virtual architecture at runtime. Running bytecode in a VM is slower than translating it to native code ahead of time because every instruction must be simulated at runtime each time it executes. In return, you get simplicity and portability. Implement your VM in, say, C, and you can run your language on any platform that has a C compiler. This is how the second interpreter we build in this book works.

或者,你可以编写虚拟机 (VM),该程序可以在运行时模拟支持虚拟架构的虚拟芯片。 在虚拟机中运行字节码比提前将其转换为本机代码要慢,因为每条指令每次执行时都必须在运行时进行模拟。 作为回报,你将获得简单性和可移植性。 例如,用 C 语言实现你的 VM,你就可以在任何具有 C 编译器的平台上运行你的语言。 这就是我们在本书中构建的第二个解释器的工作原理。

The term “virtual machine” also refers to a different kind of abstraction. A system virtual machine emulates an entire hardware platform and operating system in software. This is how you can play Windows games on your Linux machine, and how cloud providers give customers the user experience of controlling their own “server” without needing to physically allocate separate computers for each user.

术语“虚拟机”也指另一种的抽象。 系统虚拟机用软件模拟整个硬件平台和操作系统。 这就是你在 Linux 计算机上玩 Windows 游戏的方式,以及云提供商如何为客户提供控制自己的“服务器”的用户体验,而无需为每个用户物理分配单独的计算机。

The kind of VMs we’ll talk about in this book are language virtual machines or process virtual machines if you want to be unambiguous.

如果你需要更明确的定义,我们将要在本书中讨论的虚拟机类型是语言虚拟机或进程虚拟机。

2.1.8 Runtime

We have finally hammered the user’s program into a form that we can execute. The last step is running it. If we compiled it to machine code, we simply tell the operating system to load the executable and off it goes. If we compiled it to bytecode, we need to start up the VM and load the program into that.

我们终于把用户的程序锤炼成了我们可以执行的形式。 最后一步是运行它。 如果我们将其编译为机器代码,我们只需告诉操作系统加载可执行文件即可。 如果我们将其编译为字节码,我们需要启动虚拟机并将程序加载到其中。

In both cases, for all but the basest of low-level languages, we usually need some services that our language provides while the program is running. For example, if the language automatically manages memory, we need a garbage collector going in order to reclaim unused bits. If our language supports “instance of” tests so you can see what kind of object you have, then we need some representation to keep track of the type of each object during execution.

在这两种情况下,对于除了最基本的低级语言之外,我们通常需要我们的语言在程序运行时提供的一些服务。 例如,如果语言自动管理内存,我们需要一个垃圾收集器来回收未使用的位存储空间。 如果我们的语言支持用 instance of 测试我们有什么类型的对象,那么我们就需要一些表示方法来跟踪执行过程中每个对象的类型。

All of this stuff is going at runtime, so it’s called, appropriately, the runtime. In a fully compiled language, the code implementing the runtime gets inserted directly into the resulting executable. In, say, Go, each compiled application has its own copy of Go’s runtime directly embedded in it. If the language is run inside an interpreter or VM, then the runtime lives there. This is how most implementations of languages like Java, Python, and JavaScript work.

所有这些东西都在运行时进行的,因此被称为运行时。 在完全编译的语言中,实现运行时的代码会直接插入到生成的可执行文件中。 比如说,在 Go 中,每个编译后的应用程序都直接嵌入了自己的 Go 运行时副本。 如果语言在解释器或虚拟机内运行,那么运行时就在解释器或虚拟机里。 这就是 Java、Python 和 JavaScript 等大多数语言实现的工作方式。

2.2 Shortcuts and Alternate Routes

That’s the long path covering every possible phase you might implement. Many languages do walk the entire route, but there are a few shortcuts and alternate paths.

这是一条涵盖了你可能要实现的每个阶段的漫长道路。 许多语言确实走完了整条路线,但也有一些捷径和备选路径。

2.2.1 Single-pass compilers

单遍编译器

Some simple compilers interleave parsing, analysis, and code generation so that they produce output code directly in the parser, without ever allocating any syntax trees or other IRs. These single-pass compilers restrict the design of the language. You have no intermediate data structures to store global information about the program, and you don’t revisit any previously parsed part of the code. That means as soon as you see some expression, you need to know enough to correctly compile it.

一些简单的编译器交错进行解析、分析和代码生成,以便它们直接在解析器中生成输出代码,而无需分配任何语法树或其他 IR。 这些单遍编译器限制了语言的设计。 你没有中间数据结构来存储有关程序的全局信息,也不会重新访问任何先前解析过的代码部分。 这意味着一旦你看到某个表达式,你就需要了解足够的信息来正确地编译它。

Syntax-directed translation is a structured technique for building these all-at-once compilers. You associate an action with each piece of the grammar, usually one that generates output code. Then, whenever the parser matches that chunk of syntax, it executes the action, building up the target code one rule at a time.

语法导向翻译是一种用于构建这些一次性编译器的结构化技术。 你可以将一个操作与语法的每个片段(通常是生成输出代码的语法片段)关联起来。 然后,每当解析器匹配该语法块时,它就会执行该操作,一次构建一个规则的目标代码。

Pascal and C were designed around this limitation. At the time, memory was so precious that a compiler might not even be able to hold an entire source file in memory, much less the whole program. This is why Pascal’s grammar requires type declarations to appear first in a block. It’s why in C you can’t call a function above the code that defines it unless you have an explicit forward declaration that tells the compiler what it needs to know to generate code for a call to the later function.

Pascal 和 C 就是围绕这个限制而设计的。 当时的内存非常珍贵,有时候一个编译器甚至无法将整个源文件保存在内存中,更不用说整个程序了。 这就是为什么 Pascal 语法要求类型声明要先出现在块中。 这也是为什么在 C 语言中,你不能在定义函数的上面调用函数,除非你在前面有一个显式的声明,告诉编译器它需要知道什么,用来生成调用后面函数的代码。

2.2.2 Tree-walk interpreters

树遍历解释器

Some programming languages begin executing code right after parsing it to an AST (with maybe a bit of static analysis applied). To run the program, the interpreter traverses the syntax tree one branch and leaf at a time, evaluating each node as it goes.

一些编程语言在将代码解析为 AST 后立即开始执行代码(可能应用了一些静态分析)。 为了运行该程序,解释器每次都会遍历语法树的一个分支和叶子,并在运行过程中评估每个节点。

This implementation style is common for student projects and little languages, but is not widely used for general-purpose languages since it tends to be slow. Some people use “interpreter” to mean only these kinds of implementations, but others define that word more generally, so I’ll use the inarguably explicit tree-walk interpreter to refer to these. Our first interpreter rolls this way.

这种实现风格对于学生项目和小语言来说很常见,但没有广泛用于通用语言,因为它往往很慢。 有些人使用“解释器”仅指这一类实现,但其他人对解释器一词的定义更广泛,因此我将使用没有歧义的树遍历解释器来指代这些实现。 我们的第一个解释器就按照这样的方式实现。

A notable exception is early versions of Ruby, which were tree walkers. At 1.9, the canonical implementation of Ruby switched from the original MRI (Matz’s Ruby Interpreter) to Koichi Sasada’s YARV (Yet Another Ruby VM). YARV is a bytecode virtual machine.

一个值得注意的例外是 Ruby 的早期版本,它是树遍历类型解释器。 在 1.9 版本中,Ruby 的规范实现从最初的 MRI(Matz’s Ruby Interpreter)切换到 Koichi Sasada 的 YARV(Yet Another Ruby VM)。 YARV 是一个字节码虚拟机。

2.2.3 Transpilers

转译器

Writing a complete back end for a language can be a lot of work. If you have some existing generic IR to target, you could bolt your front end onto that. Otherwise, it seems like you’re stuck. But what if you treated some other source language as if it were an intermediate representation?

为一种语言编写完整的后端可能需要大量工作。 如果你有一些现有的通用 IR 作为目标,就可以将前端转换到该 IR 上。 否则,你可能会深陷其中。 但是,如果你将其他源语言视为中间代码,该怎么办?

You write a front end for your language. Then, in the back end, instead of doing all the work to lower the semantics to some primitive target language, you produce a string of valid source code for some other language that’s about as high level as yours. Then, you use the existing compilation tools for that language as your escape route off the mountain and down to something you can execute.

你需要为你的语言编写一个前端。 然后,在后端,你可以生成一串和你的语言级别差不多的其他语言的有效源代码字符串,而不必将所有代码向下解释到某种原始目标语言的语义。 然后,你可以使用该语言现成的编译工具作为你逃离大山的路径,并得到某些可执行的内容。

They used to call this a source-to-source compiler or a transcompiler. After the rise of languages that compile to JavaScript in order to run in the browser, they’ve affected the hipster sobriquet transpiler.

他们过去称之为源到源编译器或转译器。 在编译为 JavaScript 以便在浏览器中运行的语言兴起后,它们有了一个时髦的绰号——转译器。

The first transcompiler, XLT86, translated 8080 assembly into 8086 assembly. That might seem straightforward, but keep in mind the 8080 was an 8-bit chip and the 8086 a 16-bit chip that could use each register as a pair of 8-bit ones. XLT86 did data flow analysis to track register usage in the source program and then efficiently map it to the register set of the 8086.

第一个转编译器 XLT86 将 8080 汇编语言翻译为 8086 汇编语言。 这看起来似乎很简单,但请记住,8080 是一个 8 位芯片,而 8086 是一个 16 位芯片,可以将每个寄存器用作一对 8 位寄存器。 XLT86 通过数据流分析来跟踪源程序中寄存器的使用情况,然后有效地将其映射到8086的寄存器组。

It was written by Gary Kildall, a tragic hero of computer science if there ever was one. One of the first people to recognize the promise of microcomputers, he created PL/M and CP/M, the first high-level language and OS for them.

它的作者是加里·基尔达尔(Gary Kildall),他是计算机科学领域的悲剧英雄(如果有的话)。 他是最早认识到微型计算机前景的人之一,他创建了 PL/M 和 CP/M,这是微型计算机的第一个高级语言和操作系统。

He was a sea captain, business owner, licensed pilot, and motorcyclist. A TV host with the Kris Kristofferson-esque look sported by dashing bearded dudes in the ’80s. He took on Bill Gates and, like many, lost, before meeting his end in a biker bar under mysterious circumstances. He died too young, but sure as hell lived before he did.

他是一名船长、企业主、有执照的飞行员和摩托车手。 一位电视主持人,有着 80 年代克里斯·克里斯托弗森 (Kris Kristofferson) 式的外表,留着迷人大胡子的帅哥。 他与比尔盖茨较量,但和许多人一样,他输了,然后在一个神秘的情况下在摩托车酒吧里结束了生命。 他死得太早了,但可以肯定的是,他死之前就已经活过。

While the first transcompiler translated one assembly language to another, today, most transpilers work on higher-level languages. After the viral spread of UNIX to machines various and sundry, there began a long tradition of compilers that produced C as their output language. C compilers were available everywhere UNIX was and produced efficient code, so targeting C was a good way to get your language running on a lot of architectures.

虽然第一个转编译器是将一种汇编语言翻译成另一种汇编语言,但如今,大多数编译器都适用于更高级的语言。 在 UNIX 病毒式传播到各种各样的机器上之后,开始了编译器以 C 作为输出语言的悠久传统。 C 编译器在 UNIX 存在的任何地方都可以使用,并且可以生成高效的代码,因此以 C 为目标是让你的语言在许多体系结构上运行的好方法。

Web browsers are the “machines” of today, and their “machine code” is JavaScript, so these days it seems almost every language out there has a compiler that targets JS since that’s the main way to get your code running in a browser.

Web 浏览器是当今的“机器”,它们的“机器代码”是 JavaScript,所以现在似乎几乎所有语言都有一个以 JS 为目标的编译器,因为这是让代码在浏览器中运行的主要方式。

JS used to be the only way to execute code in a browser. Thanks to WebAssembly, compilers now have a second, lower-level language they can target that runs on the web.

JS 曾经是在浏览器中执行代码的唯一方式。 多亏了 WebAssembly,编译器现在有了第二种可以在 Web 运行的低级语言。

The front end—scanner and parser—of a transpiler looks like other compilers. Then, if the source language is only a simple syntactic skin over the target language, it may skip analysis entirely and go straight to outputting the analogous syntax in the destination language.

转译器的前端(扫描器和解析器)看起来与其他编译器相似。 然后,如果源语言只是目标语言在语法方面的换皮版本,则它可以完全跳过分析并直接输出目标语言中的类似语法。

If the two languages are more semantically different, you’ll see more of the typical phases of a full compiler including analysis and possibly even optimization. Then, when it comes to code generation, instead of outputting some binary language like machine code, you produce a string of grammatically correct source (well, destination) code in the target language.

如果两种语言在语义上有更大的不同,你将看到完整编译器的更多典型阶段,包括分析,甚至可能是优化。 然后,在代码生成时,无需输出像机器代码一样的二进制语言,而是生成一串语法正确的目标语言的源码(好吧,目标代码)。

Either way, you then run that resulting code through the output language’s existing compilation pipeline, and you’re good to go.

无论哪种方式,你都可以通过目标语言现有的编译流水线运行生成的代码。

2.2.4 Just-in-time compilation

即时编译

This last one is less a shortcut and more a dangerous alpine scramble best reserved for experts. The fastest way to execute code is by compiling it to machine code, but you might not know what architecture your end user’s machine supports. What to do?

最后一项与其说是一条捷径,不如说是一次危险的高山攀爬,最好留给专家。 执行代码的最快方法是将其编译为机器代码,但你可能不知道最终用户的计算机支持什么架构。 该怎么办?

You can do the same thing that the HotSpot Java Virtual Machine (JVM), Microsoft’s Common Language Runtime (CLR), and most JavaScript interpreters do. On the end user’s machine, when the program is loaded—either from source in the case of JS, or platform-independent bytecode for the JVM and CLR—you compile it to native code for the architecture their computer supports. Naturally enough, this is called just-in-time compilation. Most hackers just say “JIT”, pronounced like it rhymes with “fit”.

你可以做和 Java 虚拟机 HotSpot、Microsoft 的 CLR 和大多数 JavaScript 解释器相同的事情。 在终端用户的计算机上,当程序加载时(无论是从 JS 的源代码,还是与平台无关的 JVM 和 CLR 的字节码),都可以将其编译为本机代码,以适应本机支持的体系架构。 自然,这称为即时编译。 大多数黑客只是说“JIT”,发音就像与“fit”押韵一样。

The most sophisticated JITs insert profiling hooks into the generated code to see which regions are most performance critical and what kind of data is flowing through them. Then, over time, they will automatically recompile those hot spots with more advanced optimizations.

最复杂的 JIT 会将性能分析的钩子插入到生成的代码中,以查看哪些区域对性能最关键以及流经这些区域的数据类型有哪些。 然后,随着时间的推移,他们将通过更高级的优化功能自动重新编译这些热点。

This is, of course, exactly where the HotSpot JVM gets its name.

当然,这正是 HotSpot JVM 名称的由来。

2.3 Compilers and Interpreters

编译器和解释器

Now that I’ve stuffed your head with a dictionary’s worth of programming language jargon, we can finally address a question that’s plagued coders since time immemorial: What’s the difference between a compiler and an interpreter?

现在我已经给你塞满了一本字典里的编程语言术语,我们终于可以解决一个自远古以来一直困扰着程序员的问题了:编译器和解释器之间有什么区别?

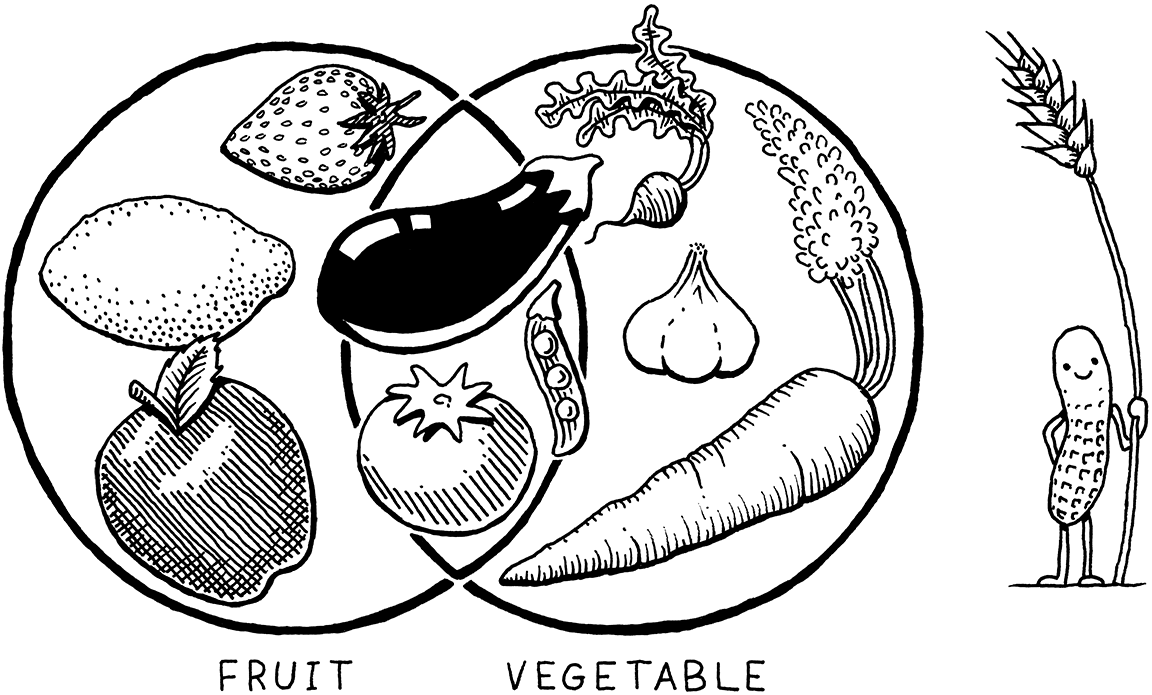

It turns out this is like asking the difference between a fruit and a vegetable. That seems like a binary either-or choice, but actually “fruit” is a botanical term and “vegetable” is culinary. One does not strictly imply the negation of the other. There are fruits that aren’t vegetables (apples) and vegetables that aren’t fruits (carrots), but also edible plants that are both fruits and vegetables, like tomatoes.

事实证明,这就像询问水果和蔬菜之间的区别一样。 这看起来像是一个二元的非此即彼的选择,但实际上“水果”是一个植物学术语,“蔬菜”是一个烹饪术语。 严格来说,一个并不意味着对另一个的否定。 有些水果不是蔬菜(苹果),有些蔬菜不是水果(胡萝卜),但也有既是水果又是蔬菜的可食用植物,例如西红柿。

Peanuts (which are not even nuts) and cereals like wheat are actually fruit, but I got this drawing wrong. What can I say, I’m a software engineer, not a botanist. I should probably erase the little peanut guy, but he’s so cute that I can’t bear to.

花生(甚至不是坚果)和小麦等谷物实际上是水果,但我画错了。 我能说什么,我是一名软件工程师,而不是植物学家。 我或许应该把那个花生小家伙抹掉,但他太可爱了,我不忍心。

Now pine nuts, on the other hand, are plant-based foods that are neither fruits nor vegetables. At least as far as I can tell.

另一方面,现在的松子是植物性食品,既不是水果也不是蔬菜。 至少据我所知。

So, back to languages:

那么,回到语言:

-

Compiling is an implementation technique that involves translating a source language to some other—usually lower-level—form. When you generate bytecode or machine code, you are compiling. When you transpile to another high-level language, you are compiling too.

-

编译是一种实现技术,涉及将源语言翻译成其他形式(通常是较低级别的形式)。 当你生成字节码或机器代码时,那就是在编译。 当你转换为另一种高级语言时,你也在编译。

-

When we say a language implementation “is a compiler”, we mean it translates source code to some other form but doesn’t execute it. The user has to take the resulting output and run it themselves.

-

相反,当我们说一个实现“是一个编译器”时,我们的意思是它会将源代码转换为其他形式,但不会执行。用户必须获取结果输出并自己运行。

-

Conversely, when we say an implementation “is an interpreter”, we mean it takes in source code and executes it immediately. It runs programs “from source”.

-

相反,当我们说一个实现“是一个解释器”时,是指它接受源代码并立即执行。 它“从源代码”运行程序。

Like apples and oranges, some implementations are clearly compilers and not interpreters. GCC and Clang take your C code and compile it to machine code. An end user runs that executable directly and may never even know which tool was used to compile it. So those are compilers for C.

就像苹果和橙子一样,某些实现显然是编译器而不是解释器。 GCC 和 Clang 获取 C 代码并将其编译为机器代码。 最终用户直接运行该可执行文件,甚至可能永远不知道使用哪个工具来编译它。 这些是 C 的编译器。

In older versions of Matz’s canonical implementation of Ruby, the user ran Ruby from source. The implementation parsed it and executed it directly by traversing the syntax tree. No other translation occurred, either internally or in any user-visible form. So this was definitely an interpreter for Ruby.

在 Matz 实现的旧版本 Ruby 规范中,用户从源代码运行 Ruby。 该实现通过遍历语法树对其解析并直接执行。 期间没有发生其他转换,无论是其内部还是以任何用户可见的形式。 所以这绝对是 Ruby 的解释器。

But what of CPython? When you run your Python program using it, the code is parsed and converted to an internal bytecode format, which is then executed inside the VM. From the user’s perspective, this is clearly an interpreter—they run their program from source. But if you look under CPython’s scaly skin, you’ll see that there is definitely some compiling going on.

但是 CPython 呢? 当你使用它运行 Python 程序时,代码会被解析并转换为内部字节码格式,然后在虚拟机内部执行。 从用户的角度来看,这显然是一个解释器——他们是从源代码开始运行他们的程序。 但如果你仔细观察 CPython 的内部,你会发现肯定有一些编译工作正在进行。

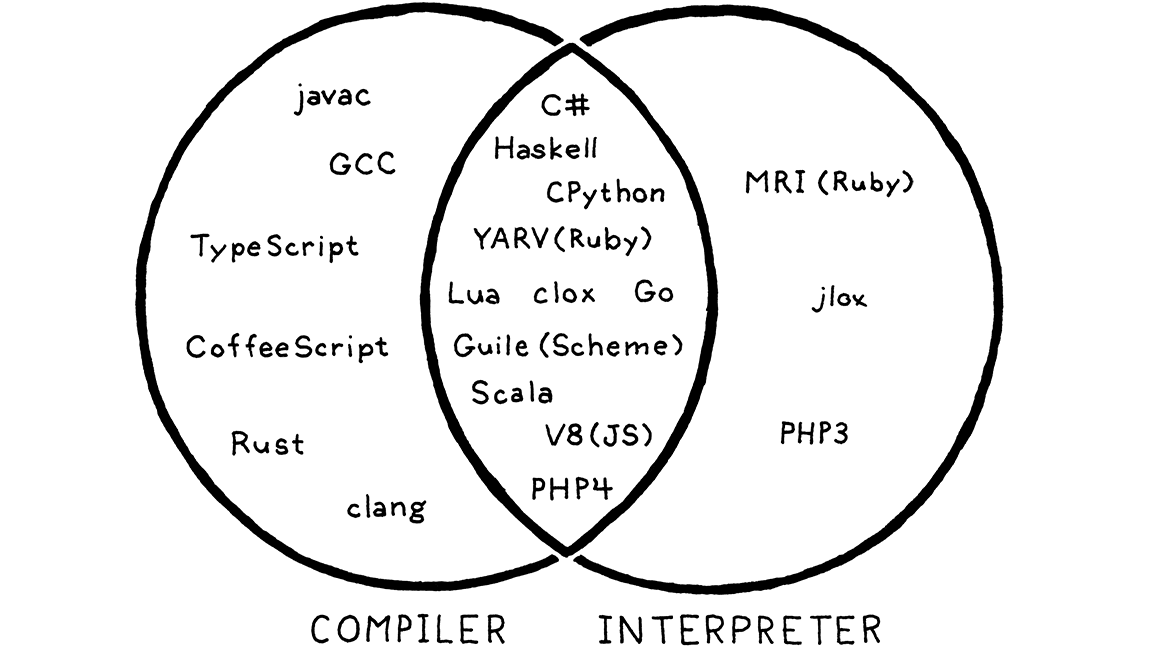

The answer is that it is both. CPython is an interpreter, and it has a compiler. In practice, most scripting languages work this way, as you can see:

答案是两者都是。 CPython 是一个解释器,同时它也有一个编译器。 实际上,大多数脚本语言都是这样工作的,如你所见:

That overlapping region in the center is where our second interpreter lives too, since it internally compiles to bytecode. So while this book is nominally about interpreters, we’ll cover some compilation too.

中心的重叠区域也是我们的第二个解释器所在的位置,因为它在内部编译为字节码。 因此,虽然这本书名义上是关于解释器的,但我们也会介绍一些编译的内容。

The Go tool is even more of a horticultural curiosity. If you run go build, it compiles your Go source code to machine code and stops. If you type go run, it does that, then immediately executes the generated executable.

Go 工具更是一个奇葩。 如果你运行

go build,它会将你的 Go 源代码编译为机器代码并停止。 如果你输入go run,它也会这么做,然后立即执行生成的可执行文件。So

gois a compiler (you can use it as a tool to compile code without running it), is an interpreter (you can invoke it to immediately run a program from source), and also has a compiler (when you use it as an interpreter, it is still compiling internally).所以

go是一个编译器(你可以将其用作一个工作来编译代码而不运行);也可以说是一个解释器(你可以调用它立即从源代码运行程序),并且还具有一个编译器(当你把它当作解释器使用时,它仍然在内部编译)。

2.4 Our Journey

That’s a lot to take in all at once. Don’t worry. This isn’t the chapter where you’re expected to understand all of these pieces and parts. I just want you to know that they are out there and roughly how they fit together.

一下子要消化的东西太多了。 不用担心。 在这一章中,你不需要理解所有这些片段和部分。 我只是想让你知道存在哪些东西,以及大致了解它们是如何组合在一起。

This map should serve you well as you explore the territory beyond the guided path we take in this book. I want to leave you yearning to strike out on your own and wander all over that mountain.

当你探索本书所引导路径之外的领域时,这张地图应该会对你有所帮助。 我希望你会渴望独自闯荡那座山。

But, for now, it’s time for our own journey to begin. Tighten your bootlaces, cinch up your pack, and come along. From here on out, all you need to focus on is the path in front of you.

但是,现在是我们自己的旅程开始的时候了。 系紧鞋带,收紧背包,走吧。 从现在开始,你需要关注的就是你面前的路。

Henceforth, I promise to tone down the whole mountain metaphor thing.

从今以后,我保证淡化整个山这个隐喻的说法。

Challenges

1) Pick an open source implementation of a language you like. Download the source code and poke around in it. Try to find the code that implements the scanner and parser. Are they handwritten, or generated using tools like Lex and Yacc? (.l or .y files usually imply the latter.)

- 选择您喜欢的语言的开源实现。 下载源代码并研究一下。 尝试找到实现扫描器和解析器的代码。 它们是手写的,还是使用 Lex 和 Yacc 等工具生成的? (

.l或.y文件通常意味着后者。)

2) Just-in-time compilation tends to be the fastest way to implement dynamically typed languages, but not all of them use it. What reasons are there to not JIT?

- 即时编译往往是实现动态类型语言的最快方法,但并非所有语言都使用它。 有哪些理由不采用 JIT?

3) Most Lisp implementations that compile to C also contain an interpreter that lets them execute Lisp code on the fly as well. Why?

- 大多数编译为 C 的 Lisp 实现还包含一个解释器,可以让它们动态执行 Lisp 代码。 为什么?