原文

https://craftinginterpreters.com/the-lox-language.html

What nicer thing can you do for somebody than make them breakfast?

—— Anthony Bourdain

还有什么能比给别人做顿早餐,更能体现你对他的好呢?

—— 安东尼·波登

We’ll spend the rest of this book illuminating every dark and sundry corner of the Lox language, but it seems cruel to have you immediately start grinding out code for the interpreter without at least a glimpse of what we’re going to end up with.

我们将用本书的其余部分来阐明 Lox 语言的每个黑暗角落,但如果让你在对目标一无所知的情况下立即开始为解释器编写代码,这似乎很残酷 。

At the same time, I don’t want to drag you through reams of language lawyering and specification-ese before you get to touch your text editor. So this will be a gentle, friendly introduction to Lox. It will leave out a lot of details and edge cases. We’ve got plenty of time for those later.

与此同时,我不想在你写代码之前就把你卷入大量的语言和规范术语中。 因此,这一节是一个温和友好的 Lox 的介绍。 它将省略很多细节和边缘情况,毕竟后面我们还有充足的时间。

A tutorial isn’t very fun if you can’t try the code out yourself. Alas, you don’t have a Lox interpreter yet, since you haven’t built one!

如果你不能亲自运行代码,那么这个教程就黯然失色。 唉,你还没有 Lox 解释器,因为你还没有构建一个!

Fear not. You can use mine.

不要害怕。 你可以用我的。

3.1 Hello, Lox

Here’s your very first taste of Lox:

这是你第一次体验 Lox:

// Your first Lox program!

print "Hello, world!";

Your first taste of Lox, the language, that is. I don’t know if you’ve ever had the cured, cold-smoked salmon before. If not, give it a try too.

这是你第一次体验 Lox 这种语言。 我不知道你以前是否吃过腌制的冷熏三文鱼。 如果没有,也尝试一下。

As that // line comment and the trailing semicolon imply, Lox’s syntax is a member of the C family. (There are no parentheses around the string because print is a built-in statement, and not a library function.)

正如 // 行注释和尾随分号所暗示的那样,Lox 的语法是 C 语言家族的成员。 (因为 print 是内置语句,而不是库函数,所以字符串两边没有括号。)

Now, I won’t claim that C has a great syntax. If we wanted something elegant, we’d probably mimic Pascal or Smalltalk. If we wanted to go full Scandinavian-furniture-minimalism, we’d do a Scheme. Those all have their virtues.

这里,我并不是想宣称 C 有很好的语法。 如果我们想要一些优雅的东西,我们可能会模仿 Pascal 或 Smalltalk。 如果我们想要完全体现斯堪的纳维亚家具的极简主义风格,我们会实现一个 Scheme。 这些都有其优点。

I’m surely biased, but I think Lox’s syntax is pretty clean. C’s most egregious grammar problems are around types. Dennis Ritchie had this idea called “declaration reflects use”, where variable declarations mirror the operations you would have to perform on the variable to get to a value of the base type. Clever idea, but I don’t think it worked out great in practice.

我当然有偏好,但我认为 Lox 的语法非常干净。 C 语言最严重的语法问题就是关于类型的。 丹尼斯·里奇(Dennis Ritchie)有一个叫“声明反映使用”的想法,其中变量声明反映了你必须对变量执行以获得基本类型值的操作。 聪明的想法,但我认为它在实践中效果不佳。

Lox doesn’t have static types, so we avoid that.

Lox 没有静态类型,所以我们避免了这种情况。

What C-like syntax has instead is something you’ll often find more valuable in a language: familiarity. I know you are already comfortable with that style because the two languages we’ll be using to implement Lox—Java and C—also inherit it. Using a similar syntax for Lox gives you one less thing to learn.

但是,类 C 语法所具有的反而是在语言中更有价值的东西:熟悉度。 我知道你已经习惯了这种风格,因为我们将用来实现 Lox 的两种语言 — Java 和 C — 也继承了这种风格。 对 Lox 使用类似的语法可以让你少学一件东西。

3.2 A High-Level Language

While this book ended up bigger than I was hoping, it’s still not big enough to fit a huge language like Java in it. In order to fit two complete implementations of Lox in these pages, Lox itself has to be pretty compact.

虽然这本书的篇幅超出了我的预期,但它仍然不够大,无法容纳像 Java 这样的庞大语言。 为了在这些页面中容纳 Lox 的两个完整实现,Lox 本身必须非常紧凑。

When I think of languages that are small but useful, what comes to mind are high-level “scripting” languages like JavaScript, Scheme, and Lua. Of those three, Lox looks most like JavaScript, mainly because most C-syntax languages do. As we’ll learn later, Lox’s approach to scoping hews closely to Scheme. The C flavor of Lox we’ll build in Part III is heavily indebted to Lua’s clean, efficient implementation.

当我想到小而有用的语言时,我想到的是高级“脚本”语言,如 JavaScript、Scheme 和 Lua。 在这三者中,Lox 看起来最像 JavaScript,主要是因为大多数 C 语法语言都是如此。 正如我们稍后将了解到的,Lox 的范围界定方法与Scheme 密切相关。 我们将在第三部分中构建的 Lox 的 C 风格很大程度上得益于 Lua 干净、高效的实现。

Now that JavaScript has taken over the world and is used to build ginormous applications, it’s hard to think of it as a “little scripting language”. But Brendan Eich hacked the first JS interpreter into Netscape Navigator in ten days to make buttons animate on web pages. JavaScript has grown up since then, but it was once a cute little language.

现在 JavaScript 已经占领了世界并被用来构建巨大的应用程序,很难将它视为一种“小型脚本语言”。 但 Brendan Eich 在十天内将第一个 JS 解释器侵入 Netscape Navigator,使网页上的按钮具有动画效果。 JavaScript 从那时起就已经成长起来,但它曾经是一种可爱的小语言。

Because Eich slapped JS together with roughly the same raw materials and time as an episode of MacGyver, it has some weird semantic corners where the duct tape and paper clips show through. Things like variable hoisting, dynamically bound

this, holes in arrays, and implicit conversions.因为 Eich 将 JS 与 MacGyver 的一集大致相同的原材料和时间放在一起,所以它有一些奇怪的语义角落,管道胶带和回形针都显示出来。 诸如变量提升、动态绑定

this、数组中的空洞和隐式转换之类的东西。I had the luxury of taking my time on Lox, so it should be a little cleaner.

毕竟,我们用来实现 Lox 的两种语言都是静态类型的。

Lox shares two other aspects with those three languages:

Lox 与这三种语言还有两个共同点:

3.2.1 Dynamic typing

Lox is dynamically typed. Variables can store values of any type, and a single variable can even store values of different types at different times. If you try to perform an operation on values of the wrong type—say, dividing a number by a string—then the error is detected and reported at runtime.

Lox 是动态类型的。 变量可以存储任何类型的值,单个变量甚至可以在不同时间存储不同类型的值。 如果你尝试对错误类型的值执行操作(例如,将数字除以字符串),在运行时就会检测到错误并报告。

There are plenty of reasons to like static types, but they don’t outweigh the pragmatic reasons to pick dynamic types for Lox. A static type system is a ton of work to learn and implement. Skipping it gives you a simpler language and a shorter book. We’ll get our interpreter up and executing bits of code sooner if we defer our type checking to runtime.

静态类型固然有很多优势,但是那些都不足以撼动 Lox 的类型选择。 因为静态类型系统需要大量的学习和实现工作。 跳过它会让你的语言学习更简单,本书也会更短。 如果我们将类型检查推迟到运行时,我们将更快地启动解释器并执行代码。

After all, the two languages we’ll be using to implement Lox are both statically typed.

毕竟,我们用来实现 Lox 的两种语言都是静态类型的。

3.2.2 Automatic memory management

High-level languages exist to eliminate error-prone, low-level drudgery, and what could be more tedious than manually managing the allocation and freeing of storage? No one rises and greets the morning sun with, “I can’t wait to figure out the correct place to call free() for every byte of memory I allocate today!”

高级语言的存在是为了消除容易出错的低级苦差事,还有什么比手动管理存储的分配和释放更乏味的呢? 没有人会在起床迎接早晨的太阳时想着,“我迫不及待地想找出调用 free() 的正确位置,来释放掉今天我在内存中申请的每个字节!”

There are two main techniques for managing memory: reference counting and tracing garbage collection (usually just called garbage collection or GC). Ref counters are much simpler to implement—I think that’s why Perl, PHP, and Python all started out using them. But, over time, the limitations of ref counting become too troublesome. All of those languages eventually ended up adding a full tracing GC, or at least enough of one to clean up object cycles.

管理内存有两种主要技术:引用计数和跟踪垃圾收集(通常简称为垃圾收集或GC)。 引用计数器的实现要简单得多——我认为这就是 Perl、PHP 和 Python 最初使用它们的原因。 但是,随着时间的推移,引用计数的局限性变成了一个大麻烦。 所有这些语言最终都添加了完整的跟踪 GC,或者至少足以清理对象的循环引用的管理方式。

In practice, ref counting and tracing are more ends of a continuum than opposing sides. Most ref counting systems end up doing some tracing to handle cycles, and the write barriers of a generational collector look a bit like retain calls if you squint.

在实践中,引用计数和追踪 GC 更像是一个连续体的两端而不是对立面。 大多数引用计数系统最终都会进行一些跟踪来处理循环,如果你仔细观察的话,分代收集器的写屏障看起来有点像保留调用。

For lots more on this, see “A Unified Theory of Garbage Collection” (PDF).

有关更多信息,请参阅“垃圾收集的统一理论”(PDF)。

这个PDF资源已经失效了

Tracing garbage collection has a fearsome reputation. It is a little harrowing working at the level of raw memory. Debugging a GC can sometimes leave you seeing hex dumps in your dreams. But, remember, this book is about dispelling magic and slaying those monsters, so we are going to write our own garbage collector. I think you’ll find the algorithm is quite simple and a lot of fun to implement.

跟踪垃圾收集听上去令人闻风丧胆。 在原始内存的层面上工作是有点折磨人的。 调试 GC 有时会让你在梦中也能看到 hex dumps。 但是,请记住,这本书是关于驱散魔法并杀死那些怪物的,所以我们将编写自己的垃圾收集器。 我想你会发现这个算法非常简单,而且实现起来很有趣。

3.3 Data Types

In Lox’s little universe, the atoms that make up all matter are the built-in data types. There are only a few:

在 Lox 的小宇宙中,构成所有物质的原子是内置的数据类型。 只有几个:

-

Booleans. You can’t code without logic and you can’t logic without Boolean values. “True” and “false”, the yin and yang of software. Unlike some ancient languages that repurpose an existing type to represent truth and falsehood, Lox has a dedicated Boolean type. We may be roughing it on this expedition, but we aren’t savages.

-

Booleans. 没有逻辑就无法编码,没有布尔值就没有逻辑。 “真”与“假”,就是软件的阴与阳。 与某些古早语言重新利用现有类型来表示真与假不同,Lox 有专用的布尔类型。 我们在这次探险中可能会有些粗暴,但我们不是野蛮人。

Boolean variables are the only data type in Lox named after a person, George Boole, which is why “Boolean” is capitalized. He died in 1864, nearly a century before digital computers turned his algebra into electricity. I wonder what he’d think to see his name all over billions of lines of Java code.

布尔变量是 Lox 中唯一以人名 George Boole 命名的数据类型,这就是“Boolean”大写的原因。 他于 1864 年去世,比数字计算机将他的代数转化为电子信息早了近一个世纪。 我很好奇他看到自己的名字遍布数十亿行 Java 代码时会作何感想。

There are two Boolean values, obviously, and a literal for each one.

显然,有两个布尔值,每个布尔值都有一个字面表示。

true; // Not false.

false; // Not *not* false.

-

Numbers. Lox has only one kind of number: double-precision floating point. Since floating-point numbers can also represent a wide range of integers, that covers a lot of territory, while keeping things simple.

-

Numbers. Lox只有一种数字:双精度浮点数。 由于浮点数也可以表示各种整数,因此可以涵盖很多领域,同时又保持简单。

Full-featured languages have lots of syntax for numbers—hexadecimal, scientific notation, octal, all sorts of fun stuff. We’ll settle for basic integer and decimal literals.

全功能的语言会有很多数字语法——十六进制、科学记数法、八进制,以及各种有趣的东西。 我们只使用基本的整数和十进制文字。

1234; // An integer.

12.34; // A decimal number.

-

Strings. We’ve already seen one string literal in the first example. Like most languages, they are enclosed in double quotes.

-

字符串。 我们已经在第一个示例中看到了一个字符串文字。 与大多数语言一样,它们用双引号引起来。

"I am a string";

""; // The empty string.

"123"; // This is a string, not a number.

As we’ll see when we get to implementing them, there is quite a lot of complexity hiding in that innocuous sequence of characters.

我们在实现它们时会看到,在这个看起来人畜无害的字符序列中隐藏着相当多的复杂性。

-

Nil. There’s one last built-in value who’s never invited to the party but always seems to show up. It represents “no value”. It’s called

nullin many other languages. In Lox we spell itnil. (When we get to implementing it, that will help distinguish when we’re talking about Lox’snilversus Java or C’snull.) -

Nil. 还有最后一个内置值,它从未被邀请参加聚会,但似乎总是出现。 它代表“没有价值”。 在许多其他语言中被称为

null。 在 Lox 中,我们将其拼写为nil。 (当我们实现它时,这将有助于区分 Lox 的nil与 Java 或 C 的null。)

There are good arguments for not having a null value in a language since null pointer errors are the scourge of our industry. If we were doing a statically typed language, it would be worth trying to ban it. In a dynamically typed one, though, eliminating it is often more annoying than having it.

由于空指针异常是我们这个行业的祸害,因此有充分的理由支撑我们在语言实现中不支持空值。 如果我们正在开发静态类型语言,禁止空值是值得尝试的。 然而在动态类型中,消除它通常比保留它更烦人。

3.4 Expressions

If built-in data types and their literals are atoms, then expressions must be the molecules. Most of these will be familiar.

如果内置数据类型及其文字是原子,那么表达式必须是分子。 其中的大部分我们都很熟悉。

3.4.1 Arithmetic

算术运算

Lox features the basic arithmetic operators you know and love from C and other languages:

Lox 具有你在 C 和其他语言中了解和喜爱的基本算术运算符:

add + me;

subtract - me;

multiply * me;

divide / me;

The subexpressions on either side of the operator are operands. Because there are two of them, these are called binary operators. (It has nothing to do with the ones-and-zeroes use of “binary”.) Because the operator is fixed in the middle of the operands, these are also called infix operators (as opposed to prefix operators where the operator comes before the operands, and postfix where it comes after).

运算符两侧的子表达式是操作数。 因为有两个,所以称为二元运算符。 (它与“二进制”的二元 1 和 0 的使用无关。)因为运算符固定在操作数的中间,所以这些也称为中缀运算符,相对的,还有前缀运算符(运算符位于操作数之前)和后缀运算符(运算符位于操作数之后)。

There are some operators that have more than two operands and the operators are interleaved between them. The only one in wide usage is the “conditional” or “ternary” operator of C and friends:

有些运算符具有两个以上的操作数,并且运算符和操作数是交错的。 唯一广泛使用的是 C 及其相似语言中的“条件”或“三元”运算符:

condition ? thenArm : elseArm;Some call these mixfix operators. A few languages let you define your own operators and control how they are positioned—their “fixity”.

有些人称这些为 mixfix 运算符。 有一些语言允许你定义自己的运算符并控制它们的定位方式——固定的运算方式。

One arithmetic operator is actually both an infix and a prefix one. The - operator can also be used to negate a number.

有一个算术运算符既是中缀又是前缀。 - 运算符也可用于对数字求负。

-negateMe;

All of these operators work on numbers, and it’s an error to pass any other types to them. The exception is the + operator—you can also pass it two strings to concatenate them.

所有这些运算符都适用于数字,将任何其他类型传递给它们都是错误的。 但是 + 运算符是个例外,可以向其传递两个字符串来连接它们。

3.4.2 Comparison and equality

Moving along, we have a few more operators that always return a Boolean result. We can compare numbers (and only numbers), using Ye Olde Comparison Operators.

接下来还有一些始终返回布尔结果的运算符。 我们可以使用比较老的比较运算符来比较数字(并且只能比较数字)。

这个 Ye Olde 是一个假近代英语用词。

less < than;

lessThan <= orEqual;

greater > than;

greaterThan >= orEqual;

We can test two values of any kind for equality or inequality.

我们可以测试任何类型的两个值的相等或不平等。

1 == 2; // false.

"cat" != "dog"; // true.

Even different types.

也可以比较不同类型。

314 == "pi"; // false.

Values of different types are never equivalent.

不同类型的值永远不会相等。

123 == "123"; // false.

I’m generally against implicit conversions.

我通常是反对隐式转换。

3.4.3 Logical operators

The not operator, a prefix !, returns false if its operand is true, and vice versa.

取非运算符(前缀 !),如果其操作数为 true,则返回 false,反之亦然。

!true; // false.

!false; // true.

The other two logical operators really are control flow constructs in the guise of expressions. An and expression determines if two values are both true. It returns the left operand if it’s false, or the right operand otherwise.

另外两个逻辑运算符实际上是表达式形式的控制流结构。 and 表达式确定两个值是否都为 true。 如果左操作数为 false,则返回左操作数,即 false,否则返回右操作数,即 false 或者 true。

true and false; // false.

true and true; // true.

And an or expression determines if either of two values (or both) are true. It returns the left operand if it is true and the right operand otherwise.

or 表达式确定两个值中的一个(或两个)是否为真。 如果左操作数为 true,则返回左操作数,即 true,否则返回右操作数,即 false 或者 true。

false or false; // false.

true or false; // true.

I used and and or for these instead of

&&and||because Lox doesn’t use&and|for bitwise operators. It felt weird to introduce the double-character forms without the single-character ones.我使用

and和or来代替&&和||,因为 Lox 不使用&和|作为按位运算符。 引入双字符形式而不引入单字符形式感觉很奇怪。I also kind of like using words for these since they are really control flow structures and not simple operators.

同时,我也偏爱使用单词来表示这些,因为它们实际上是控制流结构而不是简单的运算符。

The reason and and or are like control flow structures is that they short-circuit. Not only does and return the left operand if it is false, it doesn’t even evaluate the right one in that case. Conversely (contrapositively?), if the left operand of an or is true, the right is skipped.

and 和 or 之所以像控制流结构是因为它们会短路。 如果左操作数为 false,and不仅是返回左操作数,它甚至不会去计算右操作数。 相反地(或者说?),如果 or 的左操作数为 true,则跳过右操作数。

3.4.4 Precedence and grouping

优先级和分组

All of these operators have the same precedence and associativity that you’d expect coming from C. (When we get to parsing, we’ll get way more precise about that.) In cases where the precedence isn’t what you want, you can use () to group stuff.

如你所愿,所有这些运算符都具有和 C 语言相同的优先级和结合性。(当我们开始解析时,会进行更详细地说明。)如果默认优先级不符合你的期望,可以使用 () 进行分组。

var average = (min + max) / 2;

Since they aren’t very technically interesting, I’ve cut the remainder of the typical operator menagerie out of our little language. No bitwise, shift, modulo, or conditional operators. I’m not grading you, but you will get bonus points in my heart if you augment your own implementation of Lox with them.

我把其他典型的操作符从我们的小语言中去掉,因为它们在技术上不是很有趣。 没有位运算、移位、取模或条件运算符。 我不是在给你打分,但是如果你在自己的 Lox 中实现了它们,你会在我心里得到额外的加分。

Those are the expression forms (except for a couple related to specific features that we’ll get to later), so let’s move up a level.

这些都是表达式形式(除了一些与我们稍后将讨论的特性相关的形式),所以让我们继续。

3.5 Statements

语句

Now we’re at statements. Where an expression’s main job is to produce a value, a statement’s job is to produce an effect. Since, by definition, statements don’t evaluate to a value, to be useful they have to otherwise change the world in some way—usually modifying some state, reading input, or producing output.

现在我们来看语句。 表达式的主要工作是产生一个值,而语句的主要工作是产生一个效果。 因为根据定义,语句不会计算出一个值,所以要想有用,它们必须以某种方式改变世界——通常是修改某些状态、读取输入或产生输出。

You’ve seen a couple of kinds of statements already. The first one was:

你已经看到了几种语句。 第一个是:

print "Hello, world!";

A print statement evaluates a single expression and displays the result to the user. You’ve also seen some statements like:

print 语句计算单个表达式并将结果显示给用户。 你还看到过一些语句,例如:

"some expression";

Baking

将

An expression followed by a semicolon (;) promotes the expression to statement-hood. This is called (imaginatively enough), an expression statement.

以分号 (;) 结尾的表达式将提升为语句级。 这被称为(很有想象力),表达式语句。

If you want to pack a series of statements where a single one is expected, you can wrap them up in a block.

如果你想将一系列语句打包成单个语句,可以将它们包装在块中。

{

print "One statement.";

print "Two statements.";

}

Blocks also affect scoping, which leads us to the next section…

块会影响作用域,这让我们进入下一节……

3.6 Variables

You declare variables using var statements. If you omit the initializer, the variable’s value defaults to nil.

你可以使用 var 语句声明变量。 如果省略了初始化赋值,默认值为 nil。

This is one of those cases where not having

niland forcing every variable to be initialized to some value would be more annoying than dealing withnilitself.这是其中一种处理方式,如果没有

nil并强制每个变量初始化为某个值会比处理nil本身更烦人。

var imAVariable = "here is my value";

var iAmNil;

Once declared, you can, naturally, access and assign a variable using its name.

变量声明以后就可以使用变量的名称访问和赋值。

var breakfast = "bagels";

print breakfast; // "bagels".

breakfast = "beignets";

print breakfast; // "beignets".

Can you tell that I tend to work on this book in the morning before I’ve had anything to eat?

你能看出我倾向于在早上吃东西之前写这本书吗?

I won’t get into the rules for variable scope here, because we’re going to spend a surprising amount of time in later chapters mapping every square inch of the rules. In most cases, it works like you would expect coming from C or Java.

我不会在这里讨论变量作用域的规则,因为我们将在后面的章节中花费大量的时间来详细描述每一条规则。 在大多数情况下,如你所愿,它的工作方式就像 C 或 Java 的那样。

3.7 Control Flow

It’s hard to write useful programs if you can’t skip some code or execute some more than once. That means control flow. In addition to the logical operators we already covered, Lox lifts three statements straight from C.

如果你无法跳过某些代码或多次执行某些代码,就很难写出有用的程序。 这意味着控制流必不可少。 除了我们已经介绍过的逻辑运算符之外,Lox 还直接从 C 语言中借鉴了三条语句。

We already have

andandorfor branching, and we could use recursion to repeat code, so that’s theoretically sufficient. It would be pretty awkward to program that way in an imperative-styled language, though.我们已经有了

and和or可以进行分支处理,并且我们可以使用递归来重复执行代码,所以理论上这就足够了。 不过,在命令式语言中以这种方式进行编程会非常尴尬。Scheme, on the other hand, has no built-in looping constructs. It does rely on recursion for repetition. Smalltalk has no built-in branching constructs, and relies on dynamic dispatch for selectively executing code.

另一方面,

Scheme没有内置的循环结构。 它确实依赖于递归来重复执行代码。Smalltalk没有内置的分支结构,并且依赖动态调度来选择性地执行代码。

An if statement executes one of two statements based on some condition.

if 语句根据某些条件执行两个语句中的一条。

if (condition) {

print "yes";

} else {

print "no";

}

A while loop executes the body repeatedly as long as the condition expression evaluates to true.

只要条件表达式的计算结果为 true,while 循环就会重复执行循环体。

var a = 1;

while (a < 10) {

print a;

a = a + 1;

}

I left

do whileloops out of Lox because they aren’t that common and wouldn’t teach you anything that you won’t already learn fromwhile. Go ahead and add it to your implementation if it makes you happy. It’s your party.我没有在 Lox 中使用

do while循环体,因为它们并不常见,也没有比while多其他的含义。 如果你喜欢的话,把它加到自己的实现里吧。 你自己做主。

Finally, we have for loops.

最后,还有 for 循环。

for (var a = 1; a < 10; a = a + 1) {

print a;

}

This loop does the same thing as the previous while loop. Most modern languages also have some sort of for-in or foreach loop for explicitly iterating over various sequence types. In a real language, that’s nicer than the crude C-style for loop we got here. Lox keeps it basic.

这种循环与之前的 while 循环可以实现一样的功能。 大多数现代语言还具有某种 for-in 或 foreach 循环,用于显式迭代各种序列类型。 在真正的语言中,这比我们在这里实现的原始 C 风格的 for 循环要好。 Lox 只做最基本的功能。

This is a concession I made because of how the implementation is split across chapters. A

for-inloop needs some sort of dynamic dispatch in the iterator protocol to handle different kinds of sequences, but we don’t get that until after we’re done with control flow. We could circle back and addfor-inloops later, but I didn’t think doing so would teach you anything super interesting.这是我做出的让步,因为本书中的语言实现是按章节划分的。

for-in循环需要迭代器协议中的某种动态分派来处理不同类型的序列,但直到完成控制流之后我们才能实现这种分派。 我们可以在那之后回来添加for-in循环,但我认为这样做不会教给你什么超级有趣的东西。

3.8 Functions

A function call expression looks the same as it does in C.

函数调用表达式与 C 语言中的一样。

makeBreakfast(bacon, eggs, toast);

You can also call a function without passing anything to it.

你还可以调用函数而不向其传递任何内容。

makeBreakfast();

Unlike in, say, Ruby, the parentheses are mandatory in this case. If you leave them off, the name doesn’t call the function, it just refers to it.

与 Ruby 不同的是,无参调用也必须加括号。 如果不加括号,就不会调用该函数,只是指向该函数。

A language isn’t very fun if you can’t define your own functions. In Lox, you do that with fun.

如果你不能定义自己的函数,那么实现一种语言就没意思了。 在 Lox 中,你可以用 fun 来做到这一点。

fun printSum(a, b) {

print a + b;

}

I’ve seen languages that use

fn,fun,func, andfunction. I’m still hoping to discover afunct,functi, orfunctiosomewhere.我已经见过用

fn、fun、func和function的语言。 我仍然希望在某个地方发现funct、functi或functio。

Now’s a good time to clarify some terminology. Some people throw around “parameter” and “argument” like they are interchangeable and, to many, they are. We’re going to spend a lot of time splitting the finest of downy hairs around semantics, so let’s sharpen our words. From here on out:

现在是澄清一些术语的好时机。 有些人把 parameter 和 argument 混为一谈,好像它们可以互换,对很多人来说,确实如此。 我们将花费大量时间围绕语义对其进行细致的分析,所以让我们在这里把话说清楚:

-

An argument is an actual value you pass to a function when you call it. So a function call has an argument list. Sometimes you hear actual parameter used for these.

-

argument是调用函数时传递给函数的实际值。 所以函数调用有一个

argument列表。 有时你会听到有人称呼其为实际参数。 -

A parameter is a variable that holds the value of the argument inside the body of the function. Thus, a function declaration has a parameter list. Others call these formal parameters or simply formals.

-

parameter是一个变量,用于保存函数的主体内参数的值。 因此,一个函数声明有一个

parameter列表。 其他人将这些称为形式参数或简称为形参。

Speaking of terminology, some statically typed languages like C make a distinction between declaring a function and defining it. A declaration binds the function’s type to its name so that calls can be type-checked but does not provide a body. A definition declares the function and also fills in the body so that the function can be compiled.

说到术语,一些静态类型语言(例如 C 语言)对函数声明和函数定义进行了区分。 声明将函数的类型与其名称绑定,以便在调用时进行类型检查,但不提供函数体。 定义声明了函数并填充了函数体,以便对函数进行编译。

Since Lox is dynamically typed, this distinction isn’t meaningful. A function declaration fully specifies the function including its body.

由于 Lox 是动态类型的,因此这种区别没有意义。 一个函数声明会完整地指定函数,包括其主体。

The body of a function is always a block. Inside it, you can return a value using a return statement.

函数体始终是一个块的形式。 在函数体中,可以使用 return 语句返回一个值。

fun returnSum(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

If execution reaches the end of the block without hitting a return, it implicitly returns nil.

如果执行到达块末尾而没有发现 return,就会隐式返回 nil。

See, I told you

nilwould sneak in when we weren’t looking.看,我就说

nil会在我们不注意的时候悄无声息地潜入。

3.8.1 Closures

闭包

Functions are first class in Lox, which just means they are real values that you can get a reference to, store in variables, pass around, etc. This works:

函数在 Lox 中是一等成员,这仅意味着它们都是真实的值,你可以对这些值进行引用、存储在变量中、传递等等。比如这样:

fun addPair(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

fun identity(a) {

return a;

}

print identity(addPair)(1, 2); // Prints "3".

Since function declarations are statements, you can declare local functions inside another function.

由于函数声明是语句,因此你可以在另一个函数内声明局部函数。

fun outerFunction() {

fun localFunction() {

print "I'm local!";

}

localFunction();

}

If you combine local functions, first-class functions, and block scope, you run into this interesting situation:

如果将局部函数、一等函数和块作用域结合起来,你会遇到这种有趣的情况:

fun returnFunction() {

var outside = "outside";

fun inner() {

print outside;

}

return inner;

}

var fn = returnFunction();

fn();

Here, inner() accesses a local variable declared outside of its body in the surrounding function. Is this kosher? Now that lots of languages have borrowed this feature from Lisp, you probably know the answer is yes.

在这个例子中,inner() 访问了周围函数中在其主体外部声明的局部变量。 这样合适吗? 现在很多语言都从 Lisp 借用了这个特性,你应该也知道答案是肯定的。

For that to work, inner() has to “hold on” to references to any surrounding variables that it uses so that they stay around even after the outer function has returned. We call functions that do this closures. These days, the term is often used for any first-class function, though it’s sort of a misnomer if the function doesn’t happen to close over any variables.

为了实现这一点,inner() 必须“保留”对其使用的任何周围变量的引用,这样即使在外部函数返回以后,这些变量仍然存在。 我们把能够做到这一点的函数称为闭包。 如今,这个术语经常用于任何一等函数,尽管如果该函数没有在任何变量上闭包,那么它有点用词不当。

Peter J. Landin coined the term “closure”. Yes, he invented damn near half the terms in programming languages. Most of them came out of one incredible paper, “The Next 700 Programming Languages”.

Peter J. Landin 创造了

closure一词。 是的,他发明了编程语言中近一半的术语。 其中大部分来自一篇令人难以置信的论文,《未来 700 种编程语言》。In order to implement these kind of functions, you need to create a data structure that bundles together the function’s code and the surrounding variables it needs. He called this a “closure” because it closes over and holds on to the variables it needs.

为了实现这些类型的函数,你需要创建一个数据结构,将函数的代码及其所需的周围变量捆绑在一起。 他称其为“闭包”,因为函数闭合并保留了它所需的变量。

As you can imagine, implementing these adds some complexity because we can no longer assume variable scope works strictly like a stack where local variables evaporate the moment the function returns. We’re going to have a fun time learning how to make these work correctly and efficiently.

如你所料,实现这些会增加一些复杂性,因为我们不能再假设变量作用域严格像堆栈一样工作,如果是那样的话,其中的局部变量在函数返回时就消失了。 我们将度过一段愉快的时光,学习如何让这些正确有效地运行。

3.9 Classes

Since Lox has dynamic typing, lexical (roughly, “block”) scope, and closures, it’s about halfway to being a functional language. But as you’ll see, it’s also about halfway to being an object-oriented language. Both paradigms have a lot going for them, so I thought it was worth covering some of each.

由于 Lox 具有动态类型、词法(可以认为是“块”)作用域和闭包,因此它差不多算是一种函数式语言。 但如你所见,它也差不多算是一种面向对象的语言。 这两种语言模式都有很多优点,值得分别介绍一下。

Since classes have come under fire for not living up to their hype, let me first explain why I put them into Lox and this book. There are really two questions:

鉴于类因为名不副实而受到批评,我先解释一下为什么我将它们放入 Lox 和这本书中。 这里涉及到两个问题:

3.9.1 Why might any language want to be object oriented?

为什么任何语言都想要面向对象?

Now that object-oriented languages like Java have sold out and only play arena shows, it’s not cool to like them anymore. Why would anyone make a new language with objects? Isn’t that like releasing music on 8-track?

现在像Java这样的面向对象语言已经消失了,只能在舞台上表演,再喜欢它们就不酷了。 为什么有人会在一种新语言中加入对象? 这不是像用磁带发行音乐一样吗?

It is true that the “all inheritance all the time” binge of the ’90s produced some monstrous class hierarchies, but object-oriented programming (OOP) is still pretty rad. Billions of lines of successful code have been written in OOP languages, shipping millions of apps to happy users. Likely a majority of working programmers today are using an object-oriented language. They can’t all be that wrong.

确实,90 年代的“全继承”热潮产生了一些畸形的类层次结构,但面向对象编程(OOP)仍然相当流行。 数十亿行成功的代码都是用 OOP 语言编写的,为用户提供了数百万个应用程序。 当今大多数工作程序员可能都在使用面向对象的语言。 他们不可能都错得那么离谱。

In particular, for a dynamically typed language, objects are pretty handy. We need some way of defining compound data types to bundle blobs of stuff together.

特别是,对于动态类型语言,对象非常方便。 我们需要某种方法来定义复合数据类型,用来将大量数据捆绑在一起。

If we can also hang methods off of those, then we avoid the need to prefix all of our functions with the name of the data type they operate on to avoid colliding with similar functions for different types. In, say, Racket, you end up having to name your functions like hash-copy (to copy a hash table) and vector-copy (to copy a vector) so that they don’t step on each other. Methods are scoped to the object, so that problem goes away.

如果我们还可以将方法挂在这些函数之上,那么我们就不需要在所有函数前加上它们所操作的数据类型的名称作为前缀,以避免与不同类型的类似函数发生冲突。 比如说,在 Racket 中,你最终必须将函数命名为“hash-copy”(复制哈希表)和“vector-copy”(复制向量),这样它们就不会互相干扰。 方法的作用域仅限于对象,因此问题就消失了。

3.9.2 Why is Lox object oriented

为什么 Lox 是面向对象的?

I could claim objects are groovy but still out of scope for the book. Most programming language books, especially ones that try to implement a whole language, leave objects out. To me, that means the topic isn’t well covered. With such a widespread paradigm, that omission makes me sad.

我可以说对象很酷,但仍然超出了本书的范围。 大多数编程语言书籍,尤其是那些试图实现整个语言的书籍,都忽略了对象。 对我来说,这意味着这个主题没有被很好地涵盖。 对于应用如此广泛的模式,这种缺失让我感到难过。

Given how many of us spend all day using OOP languages, it seems like the world could use a little documentation on how to make one. As you’ll see, it turns out to be pretty interesting. Not as hard as you might fear, but not as simple as you might presume, either.

鉴于我们中有很多人整天使用 OOP 语言,这个世界似乎应该有一些关于如何制作 OOP 语言的文档。 如你所见,事实证明这非常有趣。 没有你可能担心的那么困难,但也不像你想象的那么简单。

3.9.3 Classes or prototypes

类还是原型?

When it comes to objects, there are actually two approaches to them, classes and prototypes. Classes came first, and are more common thanks to C++, Java, C#, and friends. Prototypes were a virtually forgotten offshoot until JavaScript accidentally took over the world.

当谈到对象时,实际上有两种实现方法:类和原型。 类最先出现,并且由于被 C++、Java、C# 和其他类似语言的广泛使用,类变得更加普遍。 原型实际上是一个被遗忘的分支,直到 JavaScript 意外地占领了世界。

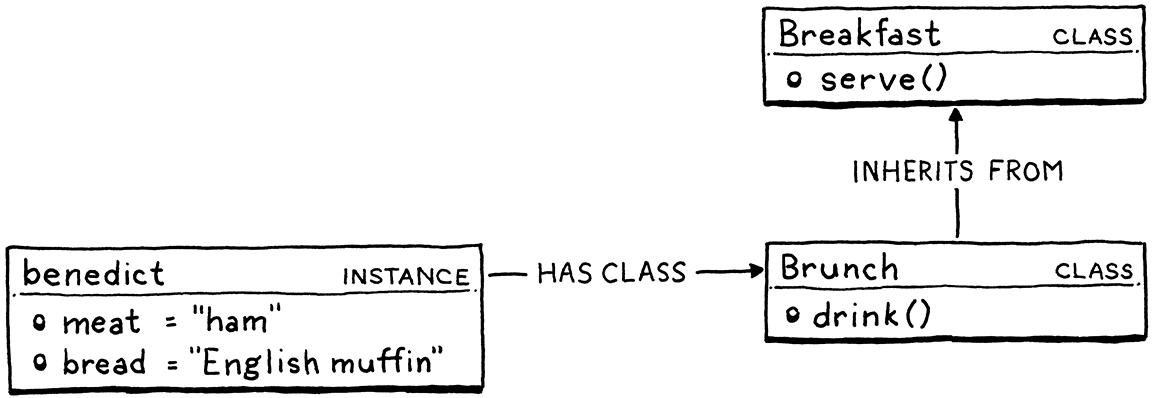

In class-based languages, there are two core concepts: instances and classes. Instances store the state for each object and have a reference to the instance’s class. Classes contain the methods and inheritance chain. To call a method on an instance, there is always a level of indirection. You look up the instance’s class and then you find the method there:

在基于类的语言中,有两个核心概念:实例和类。 实例存储每个对象的状态并具有对该实例的类的引用。 类包含方法和继承链。 要调用实例上的方法,总是存在一些中间层。 你要先查找实例的类,然后再找到其中的方法:

In a statically typed language like C++, method lookup typically happens at compile time based on the static type of the instance, giving you static dispatch. In contrast, dynamic dispatch looks up the class of the actual instance object at runtime. This is how virtual methods in statically typed languages and all methods in a dynamically typed language like Lox work.

在 C++ 这样的静态类型语言中,方法查找通常在编译时根据实例的静态类型进行,从而为你提供静态分派。 相反,动态调度在运行时查找实际实例对象的类。 这就是静态类型语言中的虚拟方法和动态类型语言(如 Lox)中的所有方法的工作原理。

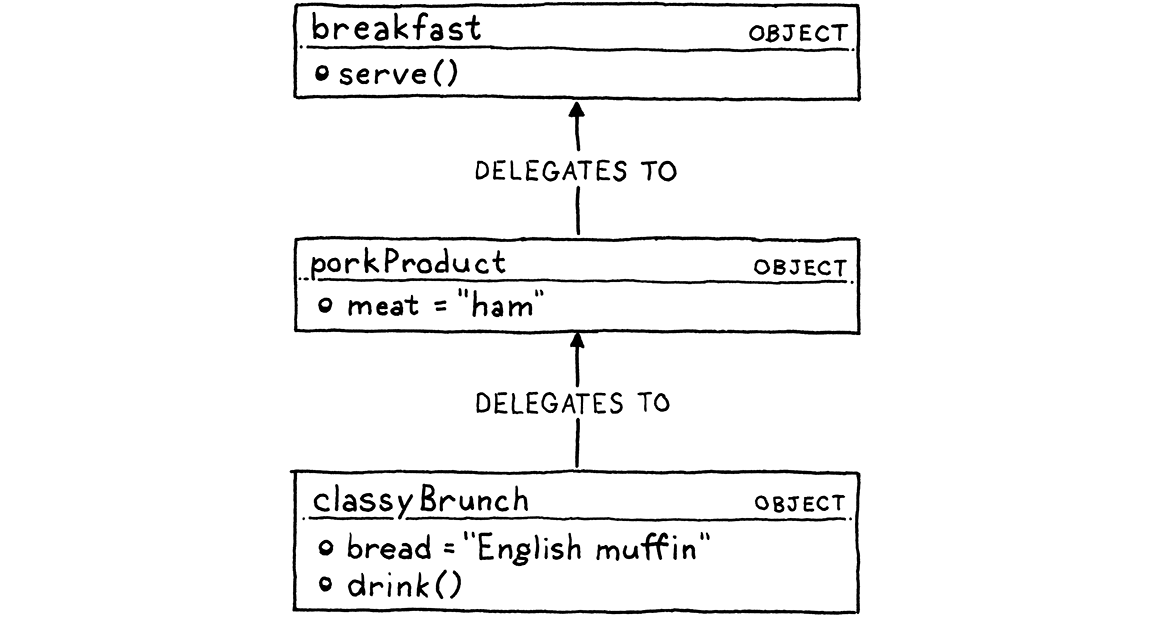

Prototype-based languages merge these two concepts. There are only objects—no classes—and each individual object may contain state and methods. Objects can directly inherit from each other (or “delegate to” in prototypal lingo):

基于原型的语言融合了这两个概念。 只有对象,没有类,每个单独的对象都可能包含状态和方法。 对象之间可以直接继承(或者用原型语言的术语,“委托”):

In practice the line between class-based and prototype-based languages blurs. JavaScript’s “constructor function” notion pushes you pretty hard towards defining class-like objects. Meanwhile, class-based Ruby is perfectly happy to let you attach methods to individual instances.

在实践中,基于类的语言和基于原型的语言之间的界限变得模糊。 JavaScript 的“构造函数”概念让你很难定义类类对象。 同时,基于类的 Ruby 非常乐意让你将方法附加到单个实例中。

This means that in some ways prototypal languages are more fundamental than classes. They are really neat to implement because they’re so simple. Also, they can express lots of unusual patterns that classes steer you away from.

这意味着在某些方面原型语言比类更基础。 它们非常容易实现,因为它们非常简单。 此外,它们还可以表达许多不寻常的模式,而这些模式是类所没有的。

But I’ve looked at a lot of code written in prototypal languages—including some of my own devising. Do you know what people generally do with all of the power and flexibility of prototypes? … They use them to reinvent classes.

但我看过很多用原型语言编写的代码——包括我自己设计的一些代码。 你知道人们通常如何利用原型的所有功能和灵活性吗? ……他们用它们来重新发明类。

I don’t know why that is, but people naturally seem to prefer a class-based (Classic? Classy?) style. Prototypes are simpler in the language, but they seem to accomplish that only by pushing the complexity onto the user. So, for Lox, we’ll save our users the trouble and bake classes right in.

我不知道这是为什么,但人们似乎自然而然地偏爱基于类的(经典?优雅?)风格。 原型在语言中更简单,但它们似乎只是通过将复杂性推给用户来实现这一点。 因此,对于 Lox,我们将为用户省去麻烦并直接把类加进来。

Larry Wall, Perl’s inventor/prophet calls this the “waterbed theory”. Some complexity is essential and cannot be eliminated. If you push it down in one place, it swells up in another.

Perl 的发明者/预言家拉里·沃尔 (Larry Wall) 将此称为“水床理论”。 某些复杂性是必不可少且无法消除的。 如果你压住一个地方,它就会在另一个地方膨胀起来。

Prototypal languages don’t so much eliminate the complexity of classes as they do make the user take that complexity by building their own class-like metaprogramming libraries.

原型语言并没有在很大程度上消除类的复杂性,而是让用户通过构建自己的近似类的元编程库来承担这种复杂性。

3.9.4 Classes in Lox

Enough rationale, let’s see what we actually have. Classes encompass a constellation of features in most languages. For Lox, I’ve selected what I think are the brightest stars. You declare a class and its methods like so:

理由已经足够了,让我们看看我们实际上有什么。 在大多数语言中,类包含了一系列的特性。 对于 Lox,我选择了我认为最炫的特性。 你可以像这样声明一个类及其方法:

class Breakfast {

cook() {

print "Eggs a-fryin'!";

}

serve(who) {

print "Enjoy your breakfast, " + who + ".";

}

}

The body of a class contains its methods. They look like function declarations but without the fun keyword. When the class declaration is executed, Lox creates a class object and stores that in a variable named after the class. Just like functions, classes are first class in Lox.

类的主体包含其方法。 它们看起来像函数声明,但没有 fun 关键字。 当执行类声明时,Lox 创建一个类对象并将其存储在以该类命名的变量中。 就像函数一样,类在 Lox 中也是一等成员。

They are still just as fun, though.

不过,它们仍然同样有趣。

// Store it in variables.

var someVariable = Breakfast;

// Pass it to functions.

someFunction(Breakfast);

Next, we need a way to create instances. We could add some sort of new keyword, but to keep things simple, in Lox the class itself is a factory function for instances. Call a class like a function, and it produces a new instance of itself.

接下来,我们需要一种创建实例的方法。 我们可以添加某种 new 关键字,但为了简单起见,在 Lox 中,类本身是实例的工厂函数。 像调用函数一样调用类,它会生成自身的新实例。

var breakfast = Breakfast();

print breakfast; // "Breakfast instance".

3.9.5 Instantiation and initialization

实例化和初始化

Classes that only have behavior aren’t super useful. The idea behind object-oriented programming is encapsulating behavior and state together. To do that, you need fields. Lox, like other dynamically typed languages, lets you freely add properties onto objects.

仅具有行为的类并不是非常有用。 面向对象编程背后的思想是将行为和状态封装在一起。 为此,你需要字段。 Lox 与其他动态类型语言一样,允许你自由地将属性添加到对象上。

breakfast.meat = "sausage";

breakfast.bread = "sourdough";

Assigning to a field creates it if it doesn’t already exist.

如果字段尚不存在,则分配给字段会先创建该字段。

If you want to access a field or method on the current object from within a method, you use good old this.

如果你想从方法内部访问当前对象的字段或方法,你可以使用古老的 this。

class Breakfast {

serve(who) {

print "Enjoy your " + this.meat + " and " +

this.bread + ", " + who + ".";

}

// ...

}

Part of encapsulating data within an object is ensuring the object is in a valid state when it’s created. To do that, you can define an initializer. If your class has a method named init(), it is called automatically when the object is constructed. Any parameters passed to the class are forwarded to its initializer.

将数据封装在对象内的目的之一是确保对象在创建时处于有效状态。 为此,你可以定义一个初始化器。 如果你的类有一个名为 init() 的方法,则在构造对象时会自动调用该方法。 传递给该类的任何参数都将转发到其初始化器。

class Breakfast {

init(meat, bread) {

this.meat = meat;

this.bread = bread;

}

// ...

}

var baconAndToast = Breakfast("bacon", "toast");

baconAndToast.serve("Dear Reader");

// "Enjoy your bacon and toast, Dear Reader."

3.9.6 Inheritance

继承

Every object-oriented language lets you not only define methods, but reuse them across multiple classes or objects. For that, Lox supports single inheritance. When you declare a class, you can specify a class that it inherits from using a less-than (<) operator.

在每个面向对象的语言中,你不仅可以定义方法,还可以在多个类或对象之间重用它们。 为此,Lox 支持单继承。 在声明类时,可以使用小于 (<) 运算符指定它继承的类。

Why the

<operator? I didn’t feel like introducing a new keyword likeextends. Lox doesn’t use:for anything else so I didn’t want to reserve that either. Instead, I took a page from Ruby and used<.为什么使用

<运算符? 我不想引入像extends这样的新关键字。 Lox 不使用:来表示其他任何内容,所以我也不想保留它。 于是,我借鉴了 Ruby 的做法,使用<。If you know any type theory, you’ll notice it’s not a totally arbitrary choice. Every instance of a subclass is an instance of its superclass too, but there may be instances of the superclass that are not instances of the subclass. That means, in the universe of objects, the set of subclass objects is smaller than the superclass’s set, though type nerds usually use

<:for that relation.如果你了解任何类型理论,你会发现这并不是一个随意的选择。 子类的每个实例也是其超类的实例,但超类的实例可能不是子类的实例。 这意味着,在对象的宇宙中,子类对象的集合小于超类对象的集合,尽管类型迷通常使用

<:来表示该关系。

class Brunch < Breakfast {

drink() {

print "How about a Bloody Mary?";

}

}

Here, Brunch is the derived class or subclass, and Breakfast is the base class or superclass.

在这个例子中,Brunch 是派生类或子类,Breakfast 是基类或超类。

Every method defined in the superclass is also available to its subclasses.

超类中定义的每个方法对其子类也可用。

var benedict = Brunch("ham", "English muffin");

benedict.serve("Noble Reader");

Even the init() method gets inherited. In practice, the subclass usually wants to define its own init() method too. But the original one also needs to be called so that the superclass can maintain its state. We need some way to call a method on our own instance without hitting our own methods.

甚至 init() 方法也会被继承。 在实践中,子类通常也想定义自己的 init() 方法。 但还需要调用原始类,以便超类可以维持其状态。 我们需要某种方法来调用超类实例上的方法,而不是触发自身实例的方法。

Lox is different from C++, Java, and C#, which do not inherit constructors, but similar to Smalltalk and Ruby, which do.

Lox 与 C++、Java 和 C# 不同,它们不继承构造函数,但与 Smalltalk 和 Ruby 类似,它们继承构造函数。

As in Java, you use super for that.

与在 Java 中一样,你可以使用 super 来实现这一点。

class Brunch < Breakfast {

init(meat, bread, drink) {

super.init(meat, bread);

this.drink = drink;

}

}

That’s about it for object orientation. I tried to keep the feature set minimal. The structure of the book did force one compromise. Lox is not a pure object-oriented language. In a true OOP language every object is an instance of a class, even primitive values like numbers and Booleans.

这就是面向对象的内容。 我尽量将功能集合保持在最少水平。 这本书的结构确实迫使我做出了妥协。 Lox 并不是一种纯粹的面向对象语言。 在真正的 OOP 语言中,每个对象都是类的实例,即使是像数字和布尔值这样的基本类型。

Because we don’t implement classes until well after we start working with the built-in types, that would have been hard. So values of primitive types aren’t real objects in the sense of being instances of classes. They don’t have methods or properties. If I were trying to make Lox a real language for real users, I would fix that.

因为我们开始使用内置类型很久之后才会去实现类,所以这一点会很难实现。 因此,从类实例的意义上来说,基本类型的值并不是真正的对象。 它们没有方法或属性。 如果以后我想让 Lox 成为真正的用户使用的语言,我会解决这个问题。

3.10 The Standard Library

标准库

We’re almost done. That’s the whole language, so all that’s left is the “core” or “standard” library—the set of functionality that is implemented directly in the interpreter and that all user-defined behavior is built on top of.

就快完成了。 这就是 Lox 语言的全貌,现在还剩下“核心”或“标准”库——这是一组直接在解释器中实现的功能,并且所有用户定义的行为都建立在这个基础上。

This is the saddest part of Lox. Its standard library goes beyond minimalism and veers close to outright nihilism. For the sample code in the book, we only need to demonstrate that code is running and doing what it’s supposed to do. For that, we already have the built-in print statement.

这是Lox最可怜的部分。 它的标准库已经超越了极简主义,接近彻底的虚无主义。 对于书中的示例代码,我们只需要证明代码正在运行并做它应该做的事情。 关于这一点,我们已经有了内置的 print 语句。

Later, when we start optimizing, we’ll write some benchmarks and see how long it takes to execute code. That means we need to track time, so we’ll define one built-in function, clock(), that returns the number of seconds since the program started.

然后,当我们开始优化时,我们将编写一些基准测试,看看执行代码需要多长时间。 这意味着我们需要跟踪时间,因此我们将定义一个内置函数 clock(),它会返回自程序启动以来的秒数。

And… that’s it. I know, right? It’s embarrassing.

嗯……就是这样。 尴尬而不失礼貌地微笑。

If you wanted to turn Lox into an actual useful language, the very first thing you should do is flesh this out. String manipulation, trigonometric functions, file I/O, networking, heck, even reading input from the user would help. But we don’t need any of that for this book, and adding it wouldn’t teach you anything interesting, so I’ve left it out.

如果你想将 Lox 变成一种真正有用的语言,你应该做的第一件事就是充实它。 比如字符串操作、三角函数、文件 I/O、网络、扩展,甚至读取用户的输入也会有帮助。 但本书不需要这些内容,而且添加它也不会教给你任何有趣的东西,所以我把它省略了。

Don’t worry, we’ll have plenty of exciting stuff in the language itself to keep us busy.

别担心,Lox 本身就有很多令人兴奋的东西够我们忙的。

Challenages

1) Write some sample Lox programs and run them (you can use the implementations of Lox in my repository). Try to come up with edge case behavior I didn’t specify here. Does it do what you expect? Why or why not?

- 编写一些 Lox 程序并运行它们(你可以使用我的存储库中的 Lox 实现)。 尝试想出我在这里没有说明的边界情况。 它的运行符合预期吗? 为什么或者为什么不?

2) This informal introduction leaves a lot unspecified. List several open questions you have about the language’s syntax and semantics. What do you think the answers should be?

- 这个非正式的介绍留下了很多未说明的内容。 列出关于该语言的语法和语义的几个开放问题。 你认为答案应该是什么?

3) Lox is a pretty tiny language. What features do you think it is missing that would make it annoying to use for real programs? (Aside from the standard library, of course.)

- Lox 是一种非常小的语言。 你认为它缺少哪些功能,导致在实际程序中使用起来很难受? (当然,除了标准库。)

Design Note: Expressions and Statements

Lox has both expressions and statements. Some languages omit the latter. Instead, they treat declarations and control flow constructs as expressions too. These “everything is an expression” languages tend to have functional pedigrees and include most Lisps, SML, Haskell, Ruby, and CoffeeScript.

Lox既有表达式又有语句。 有些语言省略了后者。 相对的,它们将声明和控制流结构也视为表达式。 这些“一切都是表达式”的语言往往具有函数式血统,包括大多数 Lisp、SML、Haskell、Ruby 和 CoffeeScript。

To do that, for each “statement-like” construct in the language, you need to decide what value it evaluates to. Some of those are easy:

为此,对于语言中的每个“类似语句”的构造,你需要决定它的计算结果是什么。 其中一些很简单:

-

An

ifexpression evaluates to the result of whichever branch is chosen. Likewise, aswitchor other multi-way branch evaluates to whichever case is picked. -

if表达式的计算结果是所选分支的结果。 同样,switch或其他多路分支取决于所选择的情况。 -

A variable declaration evaluates to the value of the variable.

-

变量声明的计算结果为变量的值。

-

A block evaluates to the result of the last expression in the sequence.

-

块的计算结果是序列中最后一个表达式的结果。

Some get a little stranger. What should a loop evaluate to? A while loop in CoffeeScript evaluates to an array containing each element that the body evaluated to. That can be handy, or a waste of memory if you don’t need the array.

有一些就比较复杂。 循环应该计算为什么值? CoffeeScript 中的 while 循环计算结果为一个数组,其中包含循环体中计算到的每个元素。 这可能很方便,但如果你不需要该数组,内存就被浪费了。

You also have to decide how these statement-like expressions compose with other expressions—you have to fit them into the grammar’s precedence table. For example, Ruby allows:

你还必须决定这些类似语句的表达式如何与其他表达式组合 - 你必须将它们放入语法的优先级表中。 例如,Ruby 允许这样写:

puts 1 + if true then 2 else 3 end + 4

Is this what you’d expect? Is it what your users expect? How does this affect how you design the syntax for your “statements”? Note that Ruby has an explicit end to tell when the if expression is complete. Without it, the + 4 would likely be parsed as part of the else clause.

这是你所期望的吗? 这是你的用户所期望的吗? 这对你设计“语句”语法的方式有何影响? 请注意,Ruby 有一个显式的 end 来表明 if 表达式何时完成。 如果没有它,+ 4 可能会被解析为 else 子句的一部分。

Turning every statement into an expression forces you to answer a few hairy questions like that. In return, you eliminate some redundancy. C has both blocks for sequencing statements, and the comma operator for sequencing expressions. It has both the if statement and the ?: conditional operator. If everything was an expression in C, you could unify each of those.

将每一个语句变成一个表达式会迫使你回答一些像这样的棘手问题。 作为回报,你消除了一些冗余。 C 语言既有用于排序语句的块,也有用于排序表达式的逗号运算符。 它同时具有 if 语句和 ?: 条件运算符。 如果 C 语言中的所有东西都是表达式,这些都可以统一起来。

Languages that do away with statements usually also feature implicit returns—a function automatically returns whatever value its body evaluates to without need for some explicit return syntax. For small functions and methods, this is really handy. In fact, many languages that do have statements have added syntax like => to be able to define functions whose body is the result of evaluating a single expression.

取消了语句的语言通常还具有隐式返回的特性,函数会自动返回其主体求值的任何值,而不需要某些显式的 return 语法。 对于小的函数和方法来说,这确实很方便。 事实上,许多有语句的语言都添加了像 => 这样的语法,以便能够定义函数体是计算单个表达式结果的函数。

But making all functions work that way can be a little strange. If you aren’t careful, your function will leak a return value even if you only intend it to produce a side effect. In practice, though, users of these languages don’t find it to be a problem.

但让所有函数都以这种方式工作可能有点奇怪。 如果你不小心,你的函数就会泄漏返回值,即使你只是想让它产生副作用。 但实际上,这些语言的用户并不认为这是一个问题。

For Lox, I gave it statements for prosaic reasons. I picked a C-like syntax for familiarity’s sake, and trying to take the existing C statement syntax and interpret it like expressions gets weird pretty fast.

对于 Lox,在其中添加语句是出于朴素的原因。 为了熟悉起见,我选择了类似 C 语言的语法,如果试图把现有的 C 语言中的语句像表达式一样解释,就会变得很奇怪。